The man driving the car had the distinct look of a grizzly about him. It was not that he was especially grizzled, more that he had a certain gravitas, a certain presence. And also, he had hands the size of a bear’s.

I remember his hands well – more than anything else about him. From my spot in the back of the car, I could see them holding the steering wheel so loosely I was not sure there was any contact between his skin and the wheel. Usually, this sort of thing wouldn’t worry me. But usually, I was not sat in the back of a stranger’s speeding car.

We had seen many grizzly bears in the days before this journey. From a boat, we had watched their humungous paws swipe above the frothy-mouthed gape of a turbulent river, we had witnessed two males stand on their hind legs and wrestle on the river bank, we had seen cubs hopscotching through the water as if life was good and easy and a playground for the taking.

In my memory, the man with the grizzly gravitas and the huge paw-hands has morphed into one of those wild bears – a planetary sort of creature, displaced from its wilderness home and now chitchatting away with his paws hovering above the steering wheel and his shaggy foot pressing, a little too hard, on the gas pedal.

“Sorry folks,” the grizzly man said as we veered so fast around a corner that I’m sure two wheels lifted off the ground. “We’re going to have to go pretty fast if we’re going to make it.”

The grizzly man, you see, was on a mission to help us.

This is what had happened –

My partner and I had been camping on the eastern coast of Vancouver Island. We had perched our tent within a thick pine forest, the sort of forest where every sound is hushed by one thousand zipped-lipped trees, and just downhill from our tent was a churning passage of sea. We had spent our days kayaking along inlets, watching bears paw along the banks, hoping for the spy-hop of a whale, bathing our city-stricken limbs in all this wild wide open.

We’d been studying in Toronto for a year before coming here, living in a grim basement apartment with one narrow window at the very end of it – a half-closed eye, too lazy to let any light in – and noisy upstairs neighbours. We lived there because rent was cheap, and we were saving up as much as we could so we could go west in the summer. We also almost exclusively ate the cheapest meal possible (pasta bake) for an entire year, so strong was the pull to a summer of adventuring; so strong was the pull of being immersed in the wild, away from all the hectic hubbub of humanity. We planned to go west and then, after a couple of months exploring, we’d go south to Costa Rica and work on a turtle conservation project for the summer.

Our time exploring west Canada went smoothly; everything worked out pretty much as we had planned. That is, until we needed to leave our campsite on Vancouver Island, get on the bus for a day-long trip to the airport, and then catch the plane to Costa Rica.

Wanting to be sure we’d make the bus in time, and in an area of Vancouver Island without public transport, we’d booked a taxi from the one taxi company that serviced this remote area. The woman was supposed to pick us up from the nearest town, and drive us an hour or so south to the bus stop.

But she wasn’t there on time. And she wasn’t there half an hour later. We called and called but nobody answered. We looked up how much time we had left to get to the bus. Not much. We looked up whether there was any other way to get to the airport on time. There wasn’t. We looked in our bank accounts to see if there was any way we could afford to buy two more flights to Costa Rica. There was not. Our bank accounts were close to empty.

“You okay?” a woman asked as she passed us on the street. We (a little frantically, and probably a little oddly, having not interacted with anybody else for a while) explained the situation. Before we knew it, we were being ushered onto the open back of a Ute. “These guys will take you to the road south,” the woman said, and then she banged the back of the truck and strolled off.

The guys in the Ute leaned out of the window and told us they were off for a fishing trip and it would be no problem for them to get us to the main road. “You in a rush?” they asked, and we said yes, and they said, “no problem, just duck when we yell duck.”

Strange instructions, but there was no time for questions – we were off. Our backpacks jiggled around the back of the truck, and so did we, gripping onto the sides to try to stop ourselves slipping. As we picked up speed, the wind – the roar of it, the current of it – swept all our panic downstream.

“Duck!” the guys yelled from the front.

We ducked. And when we popped back up, we saw a police station disappearing into the distance.

The fishermen dropped us at a gas station at the junction of the main road – a wide and winding road without a breath of traffic. “Good luck finding your next ride,” they said, and, “sorry we can’t be more help.” And then they were off.

We had been at the gas station for just a few minutes when a car, heading south, pulled in from the main road. A woman got out and headed into the shop. Naturally introverted, and far more comfortable in the company of rivers and bears than humans, we played an urgent game of Rock, Paper, Scissors to see who would have to ask her for a ride. I lost the game, and off I went to ask if these two slightly panicked, slightly dirty, bedraggled-looking campers might be able to catch a lift with her.

She said yes, but she could only take us ten minutes south. Desperate for any movement in the right direction, we hopped in her car.

I don’t remember much of that brief car journey, except first: I caught a glimpse of my wind-blown and wild reflection in her rear-view mirror and was astonished that nothing in her kind demeanour had given me a clue that I looked like a swamp creature freshly birthed from the forest. And second: that the car was very clean and nothing about me or my partner – skin, clothes, backpacks – was anywhere close to clean.

When she dropped us off on the edge of the highway, she scribbled her phone number and address on a piece of paper. “If you don’t get a lift, walk down this road until you get to a shop, then use their phone and call me,” she said. “You can stay with me until you figure out what to do next.”

The very next car that came down the main road – about half an hour later – stopped at the sight of our desperate thumbs. The grizzly man rolled down the window and asked where we were headed. It turned out he was heading to the same town, and he told us to hop in. I got in the back, my partner in front. We explained our situation to him, and how grateful we were for the lift, and this man – this wonderful, grizzly man – seemed more panicked by the whole thing than we were.

“We have half an hour until your bus leaves?!” he said, and we said yes, but don’t worry, it’s okay if we miss it, we’ll figure something out, and that is when he put his foot on the gas and said that, no matter what, he would get us on the bus.

As the car roared south, he asked about our travels, about the wildlife we’d seen, about what had brought us to Canada in the first place. When we told him we’d spent the year in Toronto his eyebrows flew up and he told us he used to live in Toronto. “Came here to escape,” he said, and there was something just a little dark at the edge of his words.

We spoke a little more about our lives as we drove that winding, forested road. We spoke about home, about fieldwork in Costa Rica, about Toronto – the beauty and the suffocation we’d felt surrounded by all those humans folded upwards into skyrise buildings, the heady chaos of that manmade galaxy, the unease of seeing one thousand lights in the night and not one of them being a star.

He told us then that he had been a detective in Toronto. A homicide detective. His grizzly hands pawed at the wheel as he said it and he took a breath as if to say something more, as if there were still words to come but they could not quite find their way out of his throat, and then he shook his head and said something like: it’s good to be here in the forest, to be here under wide open skies.

We sat in silence for a while then, all his unspoken words flocking around us.

The bus stop was empty when we arrived. We had missed it. We sat looking at that empty stop for just a few seconds before the grizzly man said, “so where’s the bus stopping next?”

It was stopping about half an hour south, adding an hour’s round trip to his journey, and we told him it was okay – we’d figure something out – but he said no, I am getting you on that bus, I am getting you to Costa Rica and to those turtles you’re going to save, and on we drove.

We went even faster this time. The forest hazed by in a whir of greens and browns, and soon the bus came into sight. We overtook it. All three of us cheered (his was the loudest).

By the time we got to the next stop, we were a good few minutes ahead of the bus. He insisted on waiting until it came, and when it did he said, “you kids have fun saving turtles,” before he turned his car around and drove away, waving his grizzly paw out the window as he drove out of view.

I still think about this gaggle of kind-hearted strangers who saved our summer. But I think the most about the detective. I think about the awful things he must have seen, the shadowy shape of them flitting around in all the empty spaces of our conversation. And I think about how wonderful it is that someone who has witnessed so much of what is dark about humans can still embody so much of what is light about us.

This is the second post of the ‘kindness chronicles’, a small act of rebellion in a world where the news is dominated by humans who are the worst of us, and who do not represent us. You can read the first post here.

If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

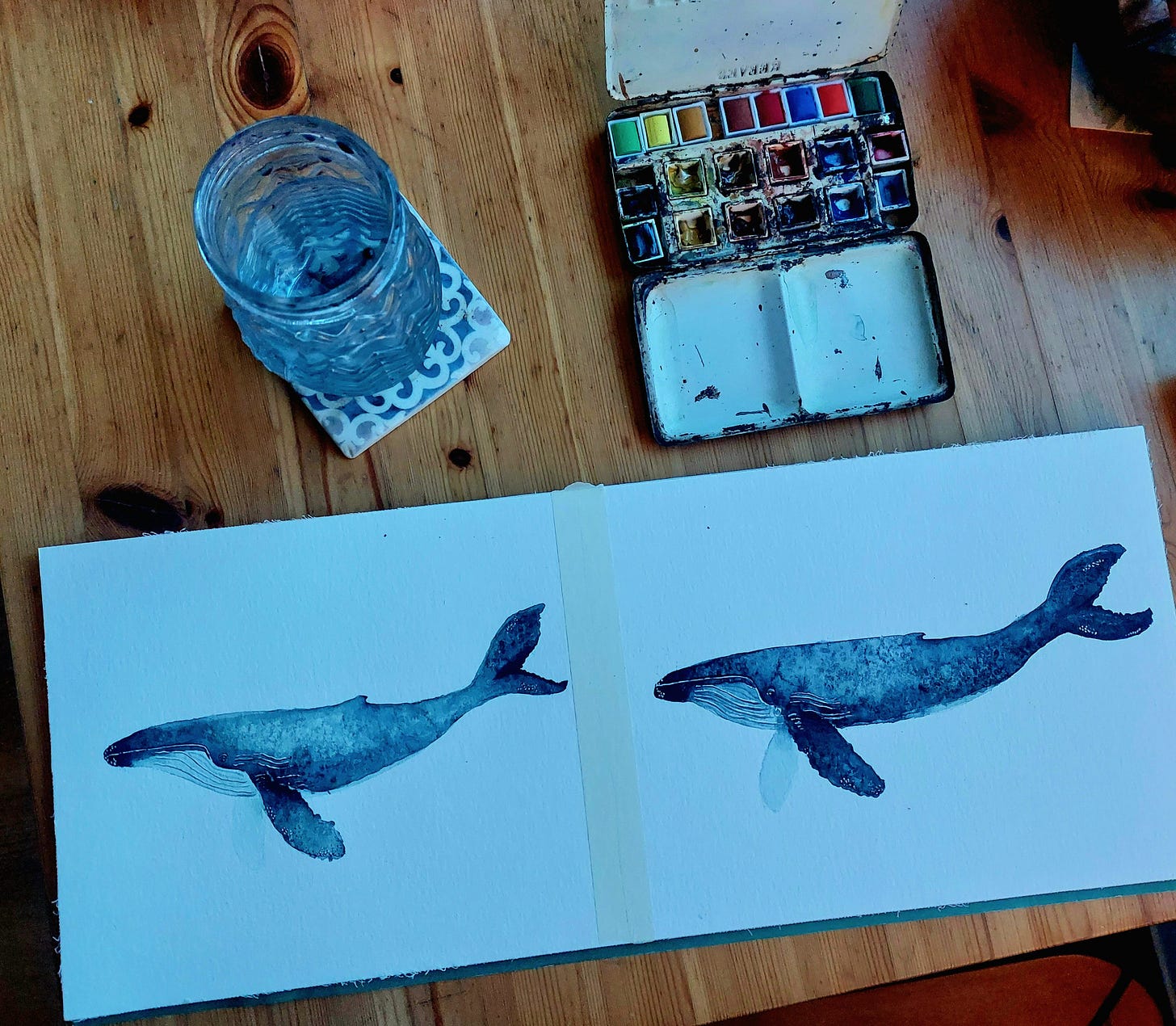

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

I am not crying, but only because I am cleaning the kitchen and my son and husband might think something was wrong, when so very much the opposite is true. My tears (that are held in my eyes for now) are for hope and kindness and belief, that perhaps, we are not lost. Thank you for writing such beauty. I found my way here from a restack by Kimberly Warner of your first Kindness Chronicle. Thank you Kimberly 💛💛✨

When there is so much horror in the world with man's inhumanity against man, it's wonderful to read such a heartwarming story and remember that there are an awful lot of lovely, kind people out there.