This morning I saw a seal’s silhouette pirouette inside a wave. An oceanic ballerina, she swirled and swivelled within the swell, before the wave curled back into itself and her shadow was lost, swallowed back into the belly of the deep.

What joy, to be taken into her world; to spend a moment of my morning meeting her here.

It is tempting to think of these wild moments as something pure, something free and disconnected from the mud of humanity, but of course this is not true. The oceans are warming because of us, and acidifying, and becoming riddled with plastic.

In the last few weeks we have learnt that, because of shareholder pressure, BP is scaling back its investment in renewable energy and turning back to fossil fuels, Trump has pulled the USA out of the Paris Agreement, glaciers are melting faster than ever before, microplastics have now been found in the Antarctic, in our brains, in the deepest ocean trenches, in the lungs of birds, and 2024 was the hottest year in human history.

The seal, dancing in this North Atlantic wave, on the northern tip of the most north-westerly Orkney Isle, lives her life within the fist of human activity, and so will her pups, and theirs. We are all connected, which is at once an incredible and terrifying thought. Human activity is inescapable for all of us, even those who have no say, no voice, no power.

We, however, have power.

I was listening to the brilliant investigative journalist

’s podcast How to Survive the Broligarchy at the exact moment I saw the seal’s shadow weaving through the wave. In fact, I was listening to the words: “we have more power than we think we have”.We all need to hear this right now. But more than that, each of us must examine it. We must examine the anatomy of our power. How is it that we can make a difference? How is it that we can shape the world into what we want it to be?

Of course, each of us will have a different answer, but what will be true for everybody is this: the small and everyday interactions we have, with one another and with our local environment, hold power. They have the power to shape the world in the same way the tides shape the shore: slowly, initially imperceptibly, but also phenomenally, and with a magnitude we cannot measure.

And this thought takes me to the final instalment of the kindness chronicles, a three-part series that I began writing a few weeks ago when news of Trump and Musk and DOGE made me crave for stories of kindness and empathy and light.

In this last instalment are five brief vignettes of human kindness (and human power).

A few months ago, I found a baby mouse – eyes still closed – in the middle of the road. It was a stormy day, and the wind held the edge of winter. I bent down, reached out my hand. In return, the blind baby mouse reached out a paw. When I put it in my palm, it curled itself up and tucked itself in.

My partner and I hadn’t anticipated quite how difficult it would be to care for a newborn mouse. Really, we needed tiny syringes and mouse formula. I posted on our island’s chat to ask whether anyone had these supplies. Nobody had a syringe small enough, but someone suggested using a fine-tipped paintbrush to feed the mouse. And nobody had mouse formula, either, but somebody said kitten formula was a good replacement, and they drove to our house to drop it off. “I hope the little mouse survives,” the woman said.

Caring for an abandoned baby mouse is really a specialist’s job, and this became clear very quickly. Every two hours - night and day - the mouse needed a feed, and the kitten formula was only a temporary fix.

I messaged a wildlife rescue group on mainland Orkney, and a woman replied instantly to say she would care for the mouse. So, the next morning I hopped on the ferry, the mouse snuggled up on a hot water bottle in my backpack, and when I got to Kirkwall I handed it over to the woman waiting on the pier.

She messaged the next day to tell me that the mouse was not thriving, and so she had passed it onto a different woman who had more experience. A couple of days later, that woman sent me a photo of her young daughter holding the baby mouse. It had opened its eyes, and it looked strong and warm and settled in the palm of this grinning girl's hand.

A few days later, the woman messaged again to say the mouse had died, and that she was very upset, and so was her daughter.

“We tried our best,” she told me, “we really did.”

And of course I was sad, but also I was thinking – what luck, that little one had, to end its life warm and full and in the capable hands of two loving humans, and to have had the chance to open its eyes and see the world, even if only for a day or two.

Last summer, three Risso’s dolphins stranded on a shallow bay on the west of the island.

We don’t have anyone trained in marine mammal rescue here, but some islanders with experience of wildlife rescue headed to the bay. They called the marine mammal medics who live on the mainland, and over the phone the medics told them how to care for the dolphins.

Wet sheets on their backs, keep them upright, stay calm.

Meanwhile, the coastguard brought the medics all the way out to our small isle.

Together, the coastguard, the medics and the islanders successfully refloated the three dolphins.

This happened just a few weeks after seventy-seven pilot whales had stranded and died on a neighbouring island. Hearing that these three dolphins survived, it felt like the island released a collective breath – a slow tide, a gentle breeze of relief.

As I was preparing to take the boat to Kirkwall a couple of months ago, I saw my neighbour walking up the road with a cat carrier.

“I heard you were going to town,” he said, “and I know it’s a huge favour, but could you possibly take this cat to the vet?”

I said of course – was it his cat? What was wrong with it? He smiled and scratched his forehead, and as he did I noticed a rather angry looking bite wound on his hand.

He told me it was not his cat, it was a feral cat he’d found the night before. It had been dragging itself along the street, its back legs not working. But, despite its paralysis, it had ferociously resisted being captured.

“A neighbour and I tried to get it last night, but it was too vicious,” he said. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it though, about the pain it must be in, so I went back out this morning to try and catch it.”

While I was on the boat with the cat, another neighbour – also headed to town – asked me about it. I told them it was a feral cat, paralysed, and I was taking it to the vet. Upon finding out I was planning to walk there, they offered me a lift. They actually came into the vets with me, concerned about the cat and wanting to help in any way they could.

The vet told us there was nothing to be done, the cat would have to be euthanised.

I messaged the neighbour who’d caught the cat, and let him know the news. He messaged back to say he was so glad it was out of pain. He added that he was making an unplanned trip on the next boat to town because the bite on his hand had become infected, and the doctor had said he needed to go straight to hospital. He glossed right over this though, and ended his message by saying, “I’m just so glad the cat’s not suffering anymore.”

Off the coast of the Isle of Skye, two fishermen heard that a humpback whale had become entangled in fishing gear. Years before, they’d signed up to a course on how to save entangled marine mammals from drowning.

When they got to the whale, they realised that it was barely able to hold itself up, so heavy was the weight of the fishing gear pulling it down. They got to work. At first, they moved the bulk of the fishing gear onto their boat to relieve the weight from the whale, and then they cut it free. It cost them two days of work to save that whale, but it seems they didn’t think twice about it. “It made us very happy to see this animal swim away alive,” one of the fishermen said in an interview. “It was the best thing.”

When I was very young, at the beach with my grandpa, I chased a crab across the rocks, and then, when I caught it, I waved it around in the air. My grandpa – a great bear of a man – took that crab gently from my enthusiastic grasp and said, “remember the crab is alive, too, and we must be gentle with all life.”

There are many layers to power. We can march, we can sign petitions, we can engage with the news, and start conversations with friends and family, and get into debates. And we should do this, if we are able, but we do not always have to go so big.

We can go small, too. We can lift a snail out of danger, we can bake bread for a neighbour, we can offer a lift to a stranger.

There is so much power – more power than we can measure – in millions of small acts of kindness.

If you’ve enjoyed the kindness chronicles, you’ll love

’s heart-warming series Stories on the Kindness of Strangers.If you look forward to the weekly between two seas newsletter, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

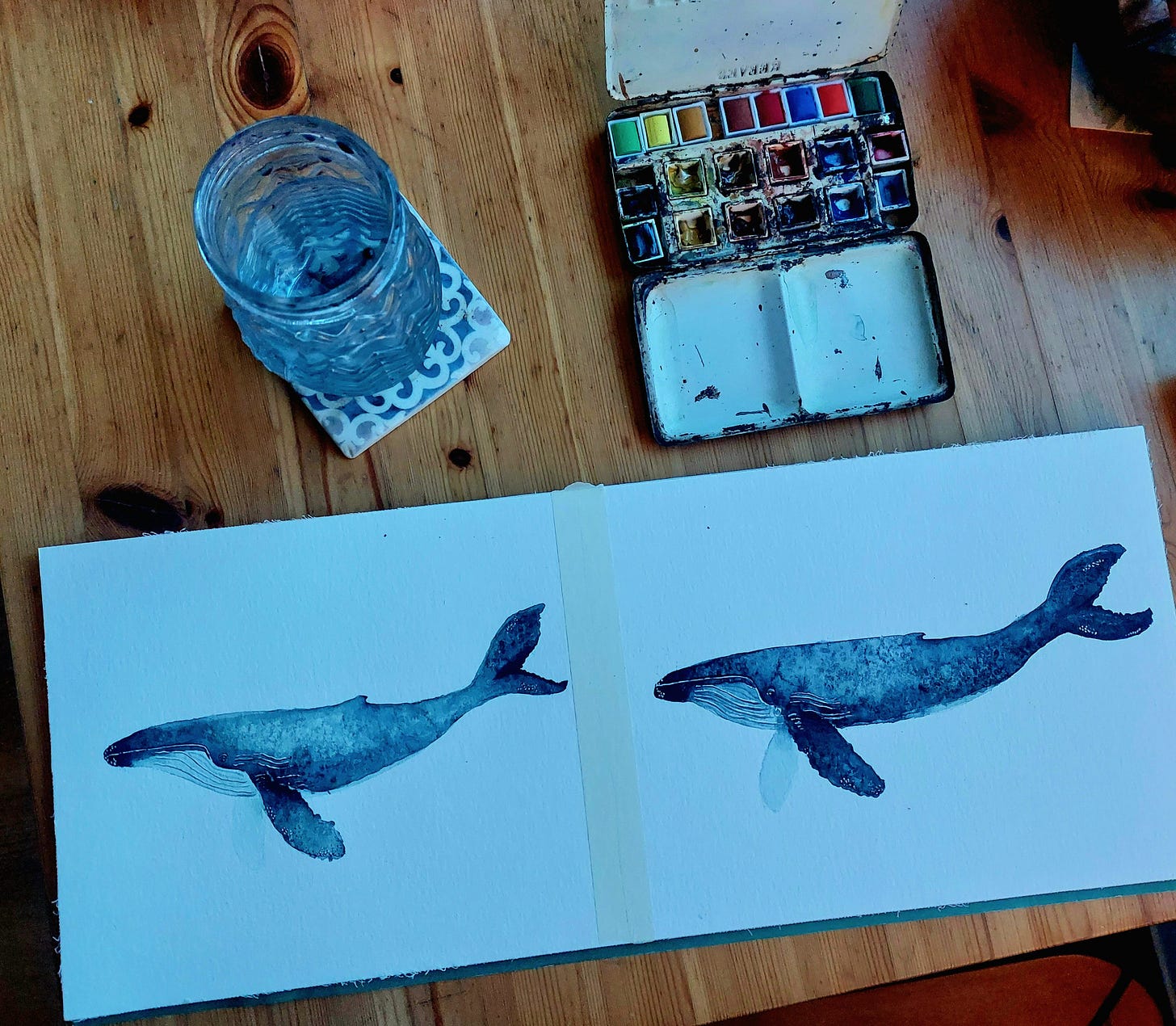

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

Beautiful, Rebecca....

We have a garden with large Green Tree Frogs - gorgeous emerald amphibians with huge eyes and a very gentle disposition (as long you aren't an insect). They roam around at night looking for food, but by daybreak they have all found places to hide - from the sun and from Monty the Diamond Python, and from the gang of Water Dragon lizards which patrol the river bank all day.

Several very clever froggies have worked out how to climb up under our vehicle, in the shady carport, and from there get into the narrow cavity under the tailgate. Totally invisible, shaded, and safe, our froggy mates happily sleep the day away there, and most days our vehicle doesn't go anywhere so it's a perfect solution.

However, we when DO need to go out - as I did today, for the 20km drive to the nearest town to get food - we have to remember to open the back hatch of the vehicle, locate the frog (and sometimes several of them) and carefully pick them up and place them in a dark damp spot in the undergrowth nearby - because a frog in a car shaped metal box in our Summer sun would quickly become a baked frog.

I think the record - a year or 2 back - was 11 frogs all huddled up together and needing to be relocated. I have a photo somewhere.

Last week I forgot to check - reached town, stopped to have a look, and there was a happy green tree frog looking back at me. SO then I had to drive around the block to find a shady place under a tree, where I could park the car without it becoming a frog oven...

In my 20s my partner was a vet tech in a rural area where she mostly called on cows. One day a very pregnant stray cat was brought in barely alive after being hit by a car. She died but they were able to deliver her premature kittens and keep them warm. Within a day all but one had died. She brought it home in a blanket lined box and I spent a good month waking every few hours and feeding her with an eye dropper. That cat lived to be almost 20 and was as mean as a rattlesnake.