Klaxon for the killer whales

And the art of finding magic.

I had not been on the island long, only a few weeks, when the first killer whales came.

I’d heard they visited these waters. Someone told me not long after we arrived that they’d once been spotted from the beach where I walk my dog each morning, and so I looked out to the rampaging February ocean each day with the hope of seeing a dorsal fin slicing through the waves.

Sometimes, in the distance, where the sea was all limb and tongue and froth dancing towards the sky, I’d see something that could have been – if I really tried to imagine it – a dorsal fin.

Sometimes, when I was feeling particularly optimistic (or, perhaps, delusional) I’d stare out to those stormy February seas and think, maybe, I had just seen the blow of a whale. I’d carry on looking, tiptoeing on the edge of wonder, until Magnus (the dog) told me he was bored, and so, reluctantly, on I would walk.

The last time I had seen killer whales, they had not been in the distance.

I was on a small research boat in Icelandic waters. A bull was right next to us; we had watched his approach through the choppy sea until the full six feet of his dorsal fin was shimmering its glorious obsidian black mere feet away. He was so close I could have touched him. When his head broke through the surface, our eyes met.

It is hard to describe the moment in any way that does it justice, but I will try. When I met his eye, my world stood still for a moment. The rock of the boat, the swill of the ocean, the call of the gulls – they were all swept to nothing. I was filled with the sort of wonder that reminds you what it means to be alive. To be small. To be part of something beautiful, edgeless, important.

For months, in my little office in a small Swedish city, I had been staring at DNA sequences extracted from killer whale skin; analysing data, creating plots, poring over maps of their geographic ranges, unpicking the odd little secrets that had been buried in their skin, and now, suddenly, here I was, eye-to-eye with this creature I had been reading about, thinking about, writing about, for months. If someone had asked me in the moment before I met the bull’s eye if I knew killer whales well, I would have said yes. I might even have said I was an expert. But I realised, in the instant I met his eye: I do not know you at all.

I learnt what was maybe the most important lesson of my scientific career in that moment. The wild and its creatures cannot be known through books and data and papers alone. Not fully. Not deeply.

My relationship with killer whales hadn’t started with data. It had started, years before my trip to Iceland, on a remote beach on the eastern coast of Vancouver Island. I was walking along the beach on an evening so calm the air felt thick with quiet. I could hear nothing but the crunch of my footsteps in the sand.

And then I heard something else: the gush of breath skittering across water. I looked out to see a whale-blow rising from the sea, followed by black backs and dorsal fins slicing through the blue. I watched the pod with a sort of pure, childlike joy.

It felt religious, somehow: the sight, the quiet, the awe.

I spent the rest of that summer reading about killer whales, and told myself that one day I would study them. And I did, partly due to luck, partly due to a sort of stubborn and unwavering dedication (some might say obsession). I studied them for my master’s degree in Sweden (and Iceland), and then, after my PhD with jackdaws, I worked in a department well-known for its killer whale research.

There are a lot of killer whale facts that might fill a person with wonder. Like the fact that they are one of the only non-human species that undergo menopause, thought to be because grandmother killer whales are crucial for the survival of their offspring and grand-offspring.

And the fact that they are likely to have cumulative culture, meaning that they build on the cultural developments made by the previous generation. We used to think only humans did this, but now we know that a few different species do – killer whales probably included.

And the fact that they speak in dialects, so that neighbouring groups have different accents, and their vocalisations are so complex that some scientists say they have language.

And the fact that they sometimes choose to work in harmony with humans. There was once a population who cooperated with human hunters: off the coast of Australia, a pod of wild killer whales would herd larger whale species towards the shore, then alert sailors living in a nearby town that they had trapped a whale. The humans would come and, together, the humans and the killer whales would hunt.

But there is something more than all of that, isn’t there? Something more than the facts.

If I had to give it words, I’d say there is just something a little bit magic about them.

Perhaps, as a scientist, I should be wary of using that word. Magic. And maybe, once, I would have been. But I have come to think one of the most beautiful parts of this life are all the fragments of mystery we have left. All that is unknowable. Mystery, and the way we wonder at it, is one of the purest joys of being here on this earth, isn’t it?

Sometimes I think I can forget that. Sometimes I have to remind myself to step into the unknown and wait, for that is when the magic comes.

Sometimes, on my bleaker days, I think we, as a species, are losing our connection with wonder, with magic. Sometimes I think this is what will kill us: that we have forgotten what it means to find magic, that we have forgotten what is sacred, that we will not try hard enough to save the very things that will save us.

I didn’t actually see the whales when they came to the island. They swam along the coast just ten minutes’ walk from my house, but I did not have my phone on me. If I had, I’d have been inundated with messages.

The island klaxon was sounding.

Every minute or so, there had been a new update across multiple messaging channels: they are in the north, they are heading east, they are going south, they are travelling at speed, come to this spot – you’ll have the best sighting, drive fast – they’re in a hurry. There must have been a small crowd gathered all along the coast, armed with binoculars and awe, straining for a sight of the giants.

When I read the messages that evening, I was, of course, disappointed I hadn’t seen the whales, but there was something else – something lighter. It was a sort of deep, nourishing happiness that so many people were so enraptured by the prospect of seeing them.

You can’t linger, someone told me later that week, when you hear they’re in these waters you just have to go, no matter what you’re in the middle of, you just have to see them, you just have to.

As they spoke, magic was on the edge of their words, in the light of their eyes, in the curve of their mouth, and I smiled, wide. I was imagining it all over again: the crowd of people who had abandoned their plans as soon as the words killer whale flashed across their phone screens, who had run to their cars and driven to the ocean, who had waited, excitedly, in the brutal weather, all for a single glimpse of black fins slicing through the blue.

All for a little glimpse of magic.

I remind myself to think of this when the world seems bleak.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this piece and would like to receive my weekly newsletter in your inbox, you can subscribe below.

My newsletter is completely free, but if you can afford £1 a week to support my writing, I would really appreciate it. As a freshly fledged freelance writer, you would be helping me a lot!

If you don’t want to pay for a subscription but would like to pay a little something for this article, you can tip me instead.

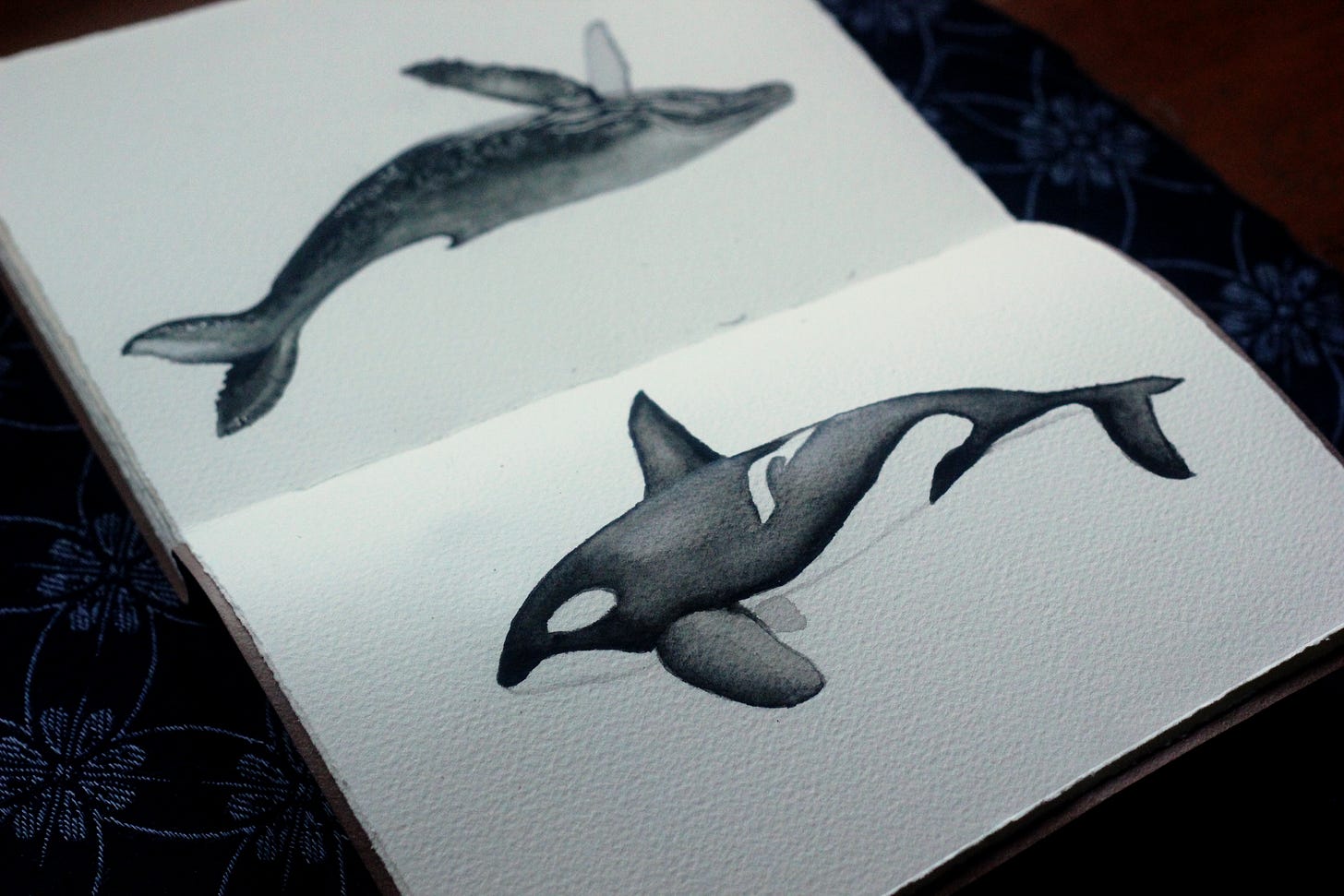

And one last thing (I promise!) - if you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling Substack, you'll receive a yearly subscription plus an original watercolour and some beachcombed treasures in the post… and my gratitude, of course! You can see the founding member option by clicking the subscribe/upgrade button above.

Just beautiful. I had a lecturer last year that said science was our way of getting closer to understanding the meaning of life. I loved that. In the spiritual circles I find myself in, initially it felt a juxtaposition to the science I loved but I began to realise that spirituality and science were the same. At 38, I’ve found myself studying for a masters in biological psychology. It has brought me full circle back to the research life I started at 21. I didn’t expect it. I haven’t yet decided whether to jump in but if I do I have been wondering whether there is an opportunity to bring a softness, a magic and a sacred understanding to the research I had before. Perhaps I research because I believe in magic and want others to believe it too. Thank you as ever for such a beautiful piece x

This is so gorgeous, I felt every word (and smelled the salt and caught the whale’s eye). Thanks for sharing your magic.