This week, a pair of ravens have adorned my skies.

Almost every time I go outside, I hear their thundering cronks. Often, they are perched on my neighbour’s roof, examining me – this odd, land-stuck ape – as I look up to them. One day, they soar above the coastline as I walk. Another, I find them rifling through sand on the beach. Interrupted, they fly from the strandline and over my head, their rumbling calls telling one another (or perhaps telling me) something I cannot decipher.

The language of ravens is something we humans do not have a good grasp of. The language of most nonhumans, in fact. Undiscovered oceans reside all around us – they ripple in the larynx of the fox, spiral in the syrinx of the sparrow, churn over the skin of the cuttlefish, crash through the feet of the elephant, torrent on the tongue of the raven.

I have always been fascinated by language. The possibilities of it; the precision, the abstraction, the solidity and ambiguity. But this love affair stems from a difficult relationship.

Painfully shy as a child, I now know I was what clinicians call “selectively mute”. What this means is that in many everyday contexts, I was – as a result of anxiety – physically unable to speak. Even if I wanted to, I could not.

Most of my primary school days were spent in silence. One teacher thought I had hearing difficulties because I would not respond to her, but I simply could not respond to her; my throat wouldn’t open to let the words out.

“She needs to speak in class,” my school reports said again and again. I remember thinking, “okay, but how?” and also, “why?”

Even in contexts when speech came easily, quiet was often my default. I suppose I never quite understood why speech was deemed necessary.

From my kitchen window, I see a raven fly behind the house. It is unusual to see one raven without the other; the pair that call the north of this island home are almost always together. But for now they are separated, and this one has found something interesting in a tussock of grass.

I watch it rootling around in the tussock for a long time, until up its head pops, triumphant, with a golf ball held delicately in its beak. It shakes its body in a way that looks very much – from my human perspective – like celebration.

And then it flies high, circles the field once, twice, three times, head cocked to the side, inkwell eye assessing the terrain below. Eventually, it lands on the opposite side of the field and buries the ball at the base of a fencepost.

It seemed that my selective mutism resolved as a teen – and on the surface, it did; if I really had to, I could speak in pretty much any context.

But in the same contexts I had once been unable to speak, I now simply forced my body into speech while dealing with the consequences. Light-headedness, darkness creeping over my vision, breathlessness. It was around the time I learnt to do this – to overrule my body’s physical manifestation of fear – that I developed a chronic pain condition, a condition that often arises in bodies that find themselves constantly in fight-or-flight.

In weekly informal work meetings throughout my twenties, exactly the sort of context in which I would have been mute as a child (lots of people, and noise, and fluorescent lights, and unclear expectations of who should be speaking when), my Fitbit would buzz and flash the words: “You’re in cardio! Keep it up!” My heartrate would be hovering around 160 beats per minute. If I had to speak, it would shoot higher. From the outside, I looked calm. On the inside, my body was roaring.

All this to say, I have long been fascinated by language, but our relationship is complicated. Speech, in particular, has never been straightforward for me.

But I think we humans are drawn to that which confounds us.

While we know that ravens have a large repertoire of calls, and that they use specific calls in specific contexts, we do not know the subtleties or nuances of their communication.

The same is true for almost every nonhuman species.

For some well-studied animals – birds, primates, whales, dolphins – we have a broad-scale understanding of when and how specific calls are used. But our understanding is basic, and often constrained by the confines of our own limited sensory systems.

Scent, vibration, ultrasonic noise, subtle movement – these are common modes of communication in nonhumans, and we are almost entirely blind to them. Often, we cannot even decode what we can easily detect (birdsong, for instance).

Just imagine it – all that language rivering around us when we step outside, all that language flowing through the quiet of the wild, all that nuanced and subtle language that we are not invited into, that we will never speak.

Even in contexts when speech comes easily, it is often difficult for me to wrangle words into what I mean to say, or even to know what it is I mean to say.

It is writing where language comes easily. To quote Joan Didion, it is where I find out what I think. If I could not write, I am not sure I would know what I think, or how to think, or even who I am.

How odd, that marking our language with something more permanent than tongue should be a force through which we not only record, but also – for some – construct, the very scaffold of who we are.

It’s all a little bit magical, isn’t it?

We do not know a lot about raven communication, but something we do know is this: they will offer objects such as stone or moss to others, and these offerings say, “will you preen me?” This is the human equivalent of: “here is some nice moss; may I have a hug?” or, “here, look at this lovely stone; will you give me a back rub?”

I wonder if the raven has stashed the golf ball for this very reason; so that later, bringing its treasure to its partner, it can speak the language of raven love. I suppose this I will never know.

I think, in essence, language has always fascinated and frustrated me because I cannot reliably grasp it. It rivers and lakes, floods and droughts, slips and stops. It lets me enter other worlds, even create new ones, but it does not always let me share my own. The language of nonhumans fascinates me for the same reason. It is also both a window and a wall.

But for me, another particular brilliance of nonhuman language is that there is no pressure to engage. To be a quiet observer is not questioned or corrected; it is the only way to be.

This, I think, is one of the reasons the wild has always felt like home to me.

You will not believe this, for I do not believe it either, but as I sit at my desk considering how to end this piece, the raven returns to the field behind my house, a perfect sphere of a golf ball in its beak.

I had been thinking: have I tied all the threads that need tying? Have I said what I wanted to say? Am I sure, even, that I know what I am saying?

But here, the raven comes with the gift of my ending, and of my meaning. For upon its tongue sits the shape of a language I will never fully grasp, but that I will listen to, quietly, and love for all the magic and mystery it holds.

As an addendum,

(of ) and recently asked me who my favourite writers are, and this essay exploring my relationship with language seemed like the perfect place to answer.My absolute favourite writers are the authors Elizabeth Strout, Maggie O’Farrell, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Kate Grenville, Mary Beth Keane and Claire Keegan, along with the poets Alice Oswald, Mary Oliver and Louise Glück.

Beyond the fact that each of these writers explore the intricacies of what it is to be human, I have been thinking about what it is that I love so much about their work. I connect with unique aspects of each, of course, but I think the two common threads are these: the way these writers break rules, and the precision with which they write.

They are each at once as precise as sculptors and as surprising as inventors. They play with language but are never greedy with words – they use only what they must. Often, there is as much in the absence of what is said as there is in the presence. And, through some combination of precision, presence, absence and play, the reader is given freedom; the reader is trusted to bring themselves to the work and to find their space within the narrative.

So, I suppose it is these qualities that I appreciate most in writing, and they are qualities I am forever striving towards. Thank you for asking ,

and . As ever, writing this has allowed me to understand something that I did not know before.Finally, when I shared a note about the raven and the golf ball earlier in the week,

of wrote this poem in response. I want to share it here, because I think it is wonderful.Thank you for reading. Would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? Your support allows me to keep writing.

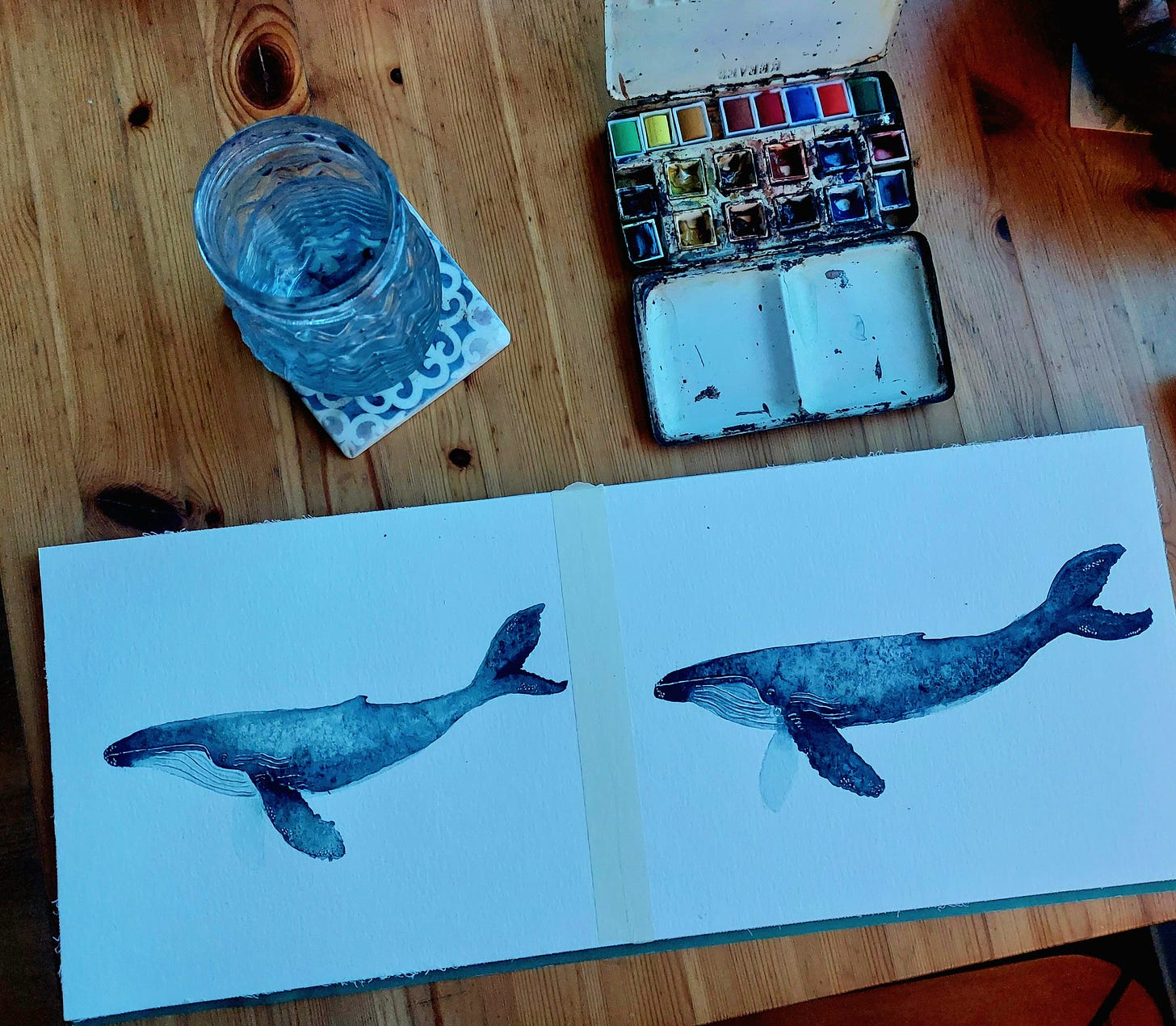

If you’d like to become a founding member (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

So much that I could select here and hold up to the light, thank you Rebecca. As a quiet child-teenager-adult, I can relate. It now occurs to me that all that sitting back while others talk is why I am an observer. Even before I reached ‘It is writing where language comes easily.’ I knew that I would say to you that it is in writing that we find joy, comfort and occasional fluency. As you say, it is strange that we invest ourselves in something more public and permanent. Quiet words, written carefully, from the heart allow us to dally with an eloquence that eludes us in daily conversation.

Always I feel like I'm breathing the freshest resonant air imaginable when I read your essays Rebecca, I am fascinated by language, by how we, and every other living creature communicates, each has their own intricate way, most we can only guess at understanding but what beauty we find in trying. I believe the form it takes is not so important, timidity is not a crime, it renders me speechless often - still! What a noisy world this would be if there weren't those that preferred pen and paper to express themselves...

Beautiful as always - Thank you xx