For the first time in a week, the wind has slackened. I have become so familiar with its riotous resistance that the air now feels thin, empty, as if there is nothing to hold me up. I walk like a newborn thing and I listen like a newborn thing, too, having heard only the demanding thrum of the storm’s tongue for a week.

The still air is misted with the delicate trill of birdsong; the music of alien lungs.

A bird lung is nothing like a human lung. On Everest, the humans who summit without oxygen masks must move very slowly as they heave their diaphragms up and down, up and down, squeezing the air for morsels of oxygen. Meanwhile, geese fly overhead. They are not breathless with altitude. Their hearts are not hectic with slow suffocation. They fly calmly, their blood oxygenated, their wingbeats strong.

A bird’s respiratory system is a wonderfully strange thing. At the end of the windpipe is an air sac, for the storage of freshly inhaled air. The sac releases this air into thin tubes where gas exchange occurs, and on the other side of the tubes the air – now depleted of oxygen – is pushed into another holding sac. Then, finally, it is released. It’s an incredibly efficient system, allowing continuous one-way airflow of fresh air.

Our lungs, on the other hand, must always have air within them or they risk collapse. This means that each of our exhales does not empty our lungs completely, and so each inhale mixes new air with old. A much less efficient system for gas exchange, but one that works for us, nonetheless. Evolution needs only “good enough”, not “perfect”.

A bird’s respiratory system is also not confined to the chest, as ours is. Instead, it spreads its tendrils through a bird’s body, lacing its way through the bones. A bird with a broken wing, if the bone is exposed to air, can have its head underwater and still breathe.

Bird bodies are bodies laced with sky. Whereas we are creatures dense as earth, they are creatures light as the big blue domes they journey through.

In the quiet air, beneath the trill and honk of spring birdsong, I go to the beach. After storms that blow in from the northwest Atlantic, as this one did, strange things are deposited on this small Scottish island. On the strandline, islanders have found twirls of bark from Newfoundland1, sea beans from the Caribbean2, many storm wrecked carcasses3, and once, a research tag that had hitchhiked on the back of a whale4.

Mostly, though, what washes up is plastic. Fishing litter, shipping litter, household litter. Ropes and nets and shotgun cartridges, Icelandic yoghurt pots, buckets from tropical waters. Sometimes, they carry open-ocean species on their backs; goose barnacles, for example5. Always, they carry a message to whoever stumbles upon them: we are bound to one another – every island, every nation, every continent, every heart; each of us a thread in a web that sprawls across this little blue dot of ours.

A bird lung is nothing like a human lung, and yet this we share: our lungs are riddled with plastic. We have known for a while that humans have microplastics in our lungs, but a study published last week also found microplastics in every bird lung analysed6. At all scales, plastic pollutes our world. From ocean, to brain. From the Antarctic, to a foetus. From the Mariana Trench, to those godlike goose lungs flying over Everest.

At a community meeting a few weeks ago, we discussed the litter that washes onto our island’s shores. A neighbour said that she often picks up litter when she is walking the coastline, but sometimes she worries she is destroying the island itself - occasionally, a dune is scaffolded with rubbish, and pulling it out makes the dune unstable, more prone to erosion. Some of these dunes are like time capsules; when the storms lap away at their sides, litter from decades ago bursts forth.

When the dunes of this isle are eventually gobbled up by the sea, the rubbish of their insides will be their only permanent remains. The same will be true of you and I and almost every creature on this planet. The parts of us that are stardust will be gifted back to the world; an exchange for our brief stint at consciousness. Our flesh will go back to the soil, our nutrients back to the earth that birthed us. Our plastic will be the one thing that does not break down (at least not for a very, very long time). The plastic that resides inside will be the most permanent legacy our bodies will leave.

Someone tells me that the plastic problem is not really a problem. They say: in a few years, we’ll have the technology to properly recycle it, or deal with the waste, so we don’t need to worry.

Behind his words, I hear Musk saying that climate change is not really a problem; in a few years we’ll all be able to move to Mars, anyway.

Behind his words, I hear people saying that we don’t need to worry about carbon emissions, the next generation is so clever and climate-aware that they’ll be sure to clean up this mess.

All these words sit snugly in the middle of a Venn diagram, where circles reading ‘ambition’, ‘optimism’ (or, one could argue, ‘delusion’), and ‘laziness’ intersect. A trio of human strength and weakness, mingling into mindsets that could mean the end of a liveable world. Not just for humans; for all of us.

A bird lung is nothing like a human lung, except that it is. Both lungs emerged from a common ancestor over 300 million years ago. In the expanse of time between then and now, they have branched, and branched, and branched again into organs that are not recognisably related, just as the creatures they reside inside are foreigners to one another, too. One dense as earth, one light as sky.

And yet, they are related. Everything is. Every single thing on this little blue dot of ours.

When astronauts view the earth from space, something transcendental can happen; an understanding that everything on our planet is connected, and everything is vulnerable, and we must treat this earth with respect and care and tenderness because it is all we have. So common is the experience that it has been given a name: the overview effect.

The thing is, I don’t think we need to go to space to have this experience. We do not need to be orbiting earth in order to have a spiritual shift towards understanding the interconnectedness and fragility of all things. We just need to look. We just need to pay attention. Because a bird lung is nothing like a human lung, except that it is, in every way that matters.

A bird lung is family, it is sky, it is ocean, it is warning.

I’d like to end with a poem, written after finding some Icelandic rubbish on the northern shore.

Thank you for reading. Would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? Your support allows me to keep writing.

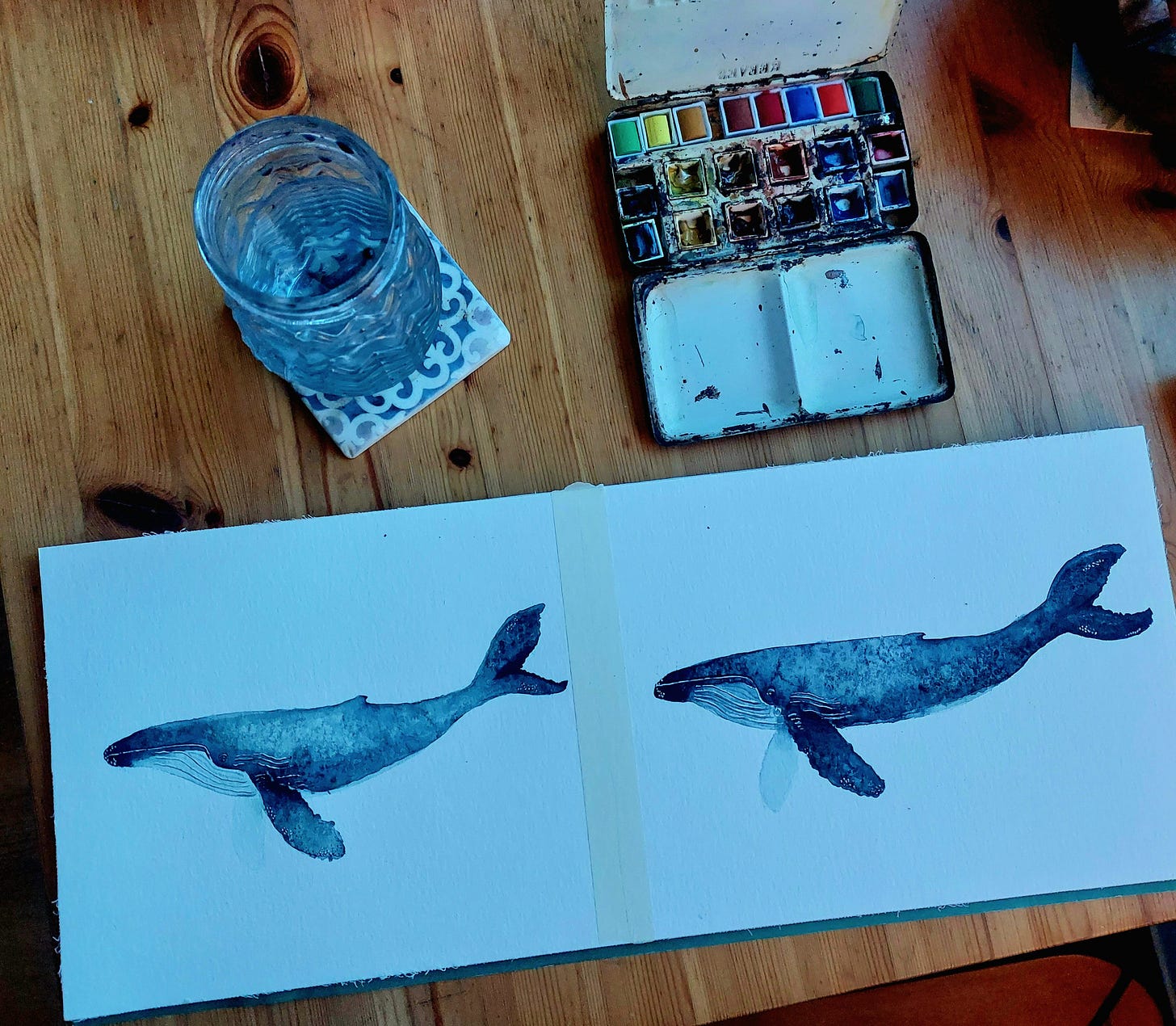

If you’d like to become a founding member (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

These twirls of bark are from the paper birch trees of Newfoundland. They start their journey from Canadian forest to these treeless Scottish isles by floating down rivers. They are then deposited into the ocean and swept along the Labrador Current. Then, the Gulf Stream picks them up. When they finally wash up on our shores, their journey has left its mark on them - they arrive with all sorts of interesting shapes and textures.

Sea beans are seeds from tropical plants. Sally Huband, based in Shetland, wrote an incredible book titled Sea Bean - one of my favourite nonfiction books. If you are interested in beachcombing, the healing that can be found in paying attention to the natural world, and just the wonder of it all, get your hands on a copy - you will love it.

I wrote a little about storm wrecked birds in my first Substack post, on this island, I am surrounded by the dead.

A beachcombing neighbour found this tag on our local beach. She tracked down the scientists it belonged to and sent it back to them. We marvelled at the thought that this tag might have travelled oceans on the back of a cetacean, and that all the secrets of its travels were stored within.

Apparently, by some magic of medieval imagination, folk once thought that barnacle geese hatched from goose barnacles (because a goose barnacle shell looks a little like a goose’s head, so I’ve heard).

You can find the study here. The lungs they analysed came from birds who had been killed anyway, as part of airport “wildlife control”. Reading this led me down a horrific rabbit-hole of learning how many birds per year are killed so that planes are at less risk of colliding with them. In the UK, it is legal for staff to shoot a whole host of bird species within 13km of an airport. They also have license to destroy nests by oiling eggs (aka, suffocating unborn chicks). There are, of course, humane alternatives that would probably deter birds from airports, e.g., by playing species-specific alarm calls. But ecological knowledge would be required to do this, and there would need to be motivation in the first place. Both, I suppose, are lacking within the industry. The more I dig into the details of our ecocidal society, the more I understand that dystopia lies in the details.

you just painted my broken heart

your gift for turning science into story, into poetry, is just awesome to watch, my friend. another wondrous meditation that somehow also exists as a call to action!