Come away to the cliffs with me.

Come to feel the wind hold your small body up.

Come to let the fulmars inspect you, come to let the wells of their eyes dwell on your strange human form (the wells of their eyes so deep and dark they could swallow you whole, flip the world inside out, gift you wings).

Come to imagine their honeycomb bones swooping through open-ocean storms. Come to imagine the white specks of their bodies gliding up the face of a forty-foot wave. Come to marvel at their small-bodied hollow-boned power.

Come to think of them in the December Atlantic, in all that expansive water, deciding it is time to come back to land.

Come to imagine them aligning their bodies to invisible forces. Come to picture that first wingbeat as they start their journey home (and the noise of it — a hushed whisper of return). Come to wonder how it feels, to be a fulmar flying back to the cliff she was raised on.

Come to witness the tsunami of their reappearance: two, ten, three hundred, one thousand.

Come to hear them chatter, cackle, caw. Come to be cloaked in their cacophony.

Come to see the way pairs sit side by side (pairs who stay together for life, which might be sixty years). Come to see the way they preen one another (tender, soft), and the way they tell their neighbours off if they shuffle a little too close. Come to witness a soap opera play out before your eyes.

Come to smell the earth-deep must of hot bird bodies.

Come to feel a gush of air rush against your cheek as they fly by.

Come to think how, two hundred and fifty years ago, they bred on only a few small Atlantic islands. Come to think of the blessing of their being here.

Come to try not to think of it (but still, think of it) — the way almost every single one of these birds has plastic in its stomach1. Come to think that when these birds die and their bodies decompose, the only mark of their lives (where no mark should be left, not for a wild thing, not for a body made of sky) will be plastic in the earth.

Come to try not to think of it (but still, think of it) — plastic, oil, drilling, broken promises, borders, bombs, a salute.

But then blink, blink, blink again, and come to think: it is not over yet.

Come to the cliffs to witness life – so much life!

Come to the cliffs to fall in love, to remind yourself what love tastes like (seasalt, gushing air, feather).

Come to the cliffs to remember all there is to live for, fight for, write for (light and flight and freedom and pounding, wild hearts).

If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

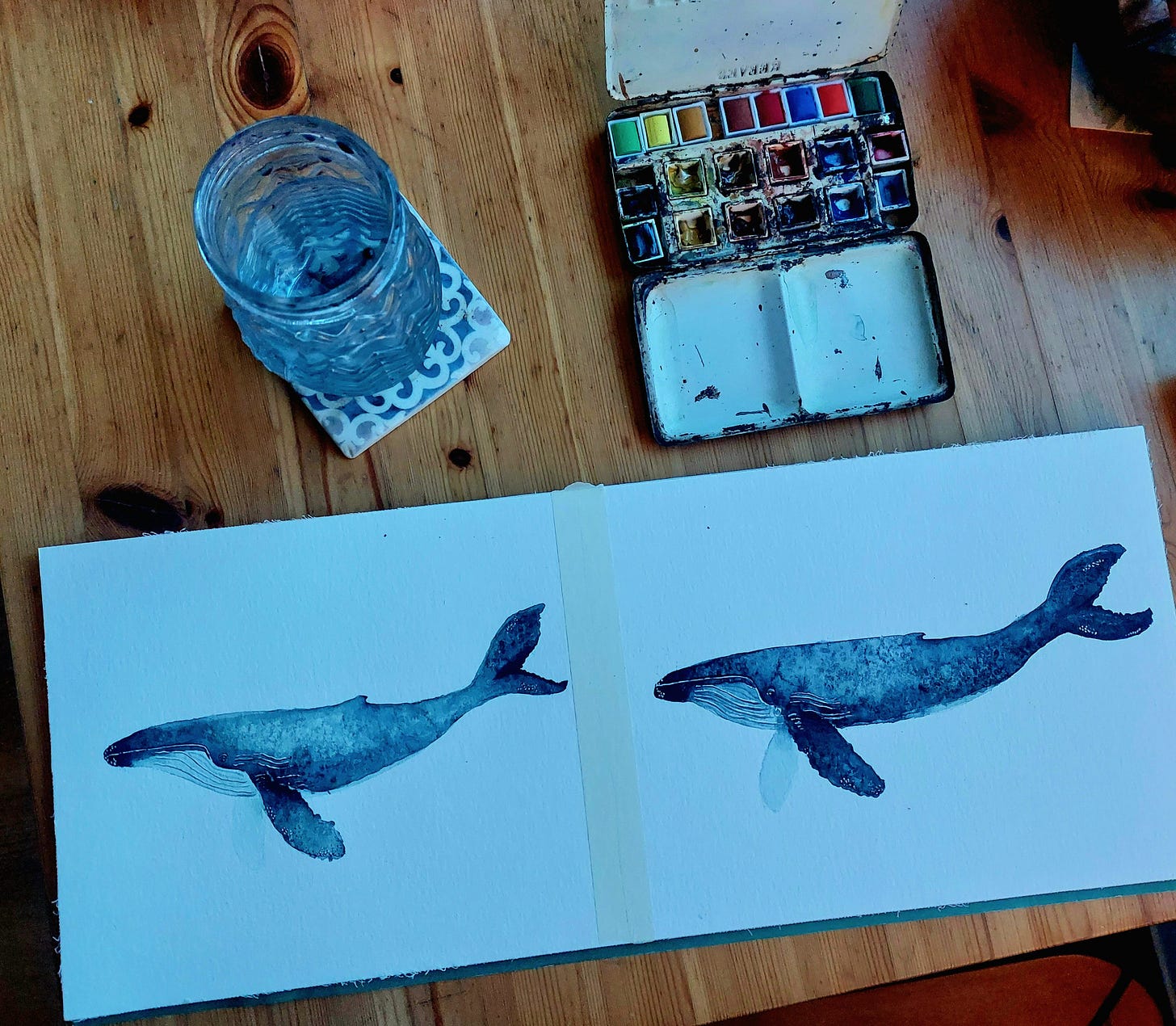

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X21002800#s0040

The recording used in the background of the voiceover was recorded by Irish Wildlife Sounds and obtained from https://xeno-canto.org/666881.

Rebecca, I see this one read out loud as you stand on a cliff, heart pounding, greeting life in her infinite form. An ode. A prayer.

I’ll tell you a secret, the other night I had a hard time sleeping and to quiet my buzzy head, I pressed my thoughts into all my favorite Substack writers, imagined each one at their desks, immersed, dedicated, present, honoring the world they inhabit with the written word. And of course, one of them was you. I fell fast asleep with a calm heart after feeling into the human heart’s gorgeous goodness.

Marvelous. Alone on watch 500 miles offshore, fulmars swoosh in across the waves. They bank steeply to shear the water. Yet black eyes stay level with the horizon. They circle round the vessel and, when calm, set down on the water in a group. The ship moves on. After a while they take flight and catch up to us to circle the rigging again. During the day their numbers grow. Out on the vast ocean, I welcome their company, not to be alone.