The haar paws gently onto the land, slinking its silken body onto shore.

The observant might spot it long before it sneaks onto soil, a distant bank of white whispering over the North Sea, but for those who are not sea-gazing it is almost always an ambush. One moment the day is clear and fair, the next the world is cocooned in sea-mist.

Spring is the season of the haar. When sun-warmed air meets cool seas, that is when its cotton body emerges.

And it is its own body. Its own animal.

It stalks and slithers and slumbers, a snow leopard of the seas: cool and calm and silent, settling itself into the land’s hidden crevices, curling its thick tail around the isle. Stories weave through the centuries of boats finding themselves, suddenly, in the thick of its body. Of children standing on shore, whistling with periwinkle shells to call them back to safety.

When I was studying evolution at the University of Toronto, I was up late one night with a friend, another international student studying evolution. We were making dinner when she said: “do you ever feel like science has become its own church, in a way?” I didn’t understand what she meant at first. Actually, I didn’t understand for years.

How could science be its own church? Science is the opposite of religion. It is about keeping an open mind until the evidence directs you. It is waiting for the world to reveal itself — empirically, through carefully designed experiments — before deciding where the truth lies. “And science works,” I said to her. “Our modern world is built on it.”

She replied that she wasn’t arguing our science is wrong, only that it’s not as open-minded as it could be. “It’s based on the assumption that everything can be empirically measured,” she said, “but what if that's not true?” We didn't have the language for it then, but I see now that she was critiquing materialism; the idea that everything real can be measured. This is the worldview that modern science is based upon.

We talked long into the night. She argued that there is a possibility that modern science has got this wrong. I argued that that seemed impossible.

I wouldn't have phrased it like this back then, but I understand now that I was stubbornly resisting the possibilities she was offering me. She was asking me to walk into the unknown, but I wanted (perhaps, back then, needed) to stay where everything was precisely where I knew it to be. I was clinging to the clear day, to a view I could make sense of, to a blue sky and a mappable landscape. She, on the other hand, was seeking the haar.

Moving through haar is a little bit of magic. It is one thing to watch it skulk across the isle from a distance, and quite another to find the animal of your body moving through the animal of its. It shifts something in the mind, but it would be hard to explain exactly what. It is something about the change of perspective, the sudden limit and limitlessness of the land you know so well. The world becomes a shadowland, a mistland, a land that is both precisely and precisely not what you know it to be.

A thin place, perhaps.

A liminal place between what is measurable, what is knowable, and what is not.

Inklings of curiosity about alternative worldviews (probably sparked by this late-night conversation with my friend) did niggle at me during my academic career. I’m sure it differs drastically across fields, but within my own academic life I felt there was not much space for this sort of curiosity. As in, I did not make the space, and neither did I see a space available.

There are, I think, a few reasons for this.

First, to question materialism is to question a fundamental building block of modern science. Therefore, in scientific circles, there is a culture of reticence about so much as entertaining non-materialist philosophies, lest somebody accuse you of undermining modern science.

Second, to question a philosophy you have built your whole life upon, your whole belief system around, is — to put it simply — terrifying. It is just easier not to.

But neither of these reasons are good enough to justify not exploring alternatives to materialism, not to enter the haar. They are just reasons to be careful and critical while exploring. To appreciate nuance. To make no assumptions.

While most (as in, almost all) scientists ascribe to a materialist worldview, a minority, often working at the frontiers of consciousness science, have rejected it.

As I said earlier, a materialist worldview suggests that everything is measurable. Consciousness, though, is a problem. We have not been able to measure it, yet at the same time it is one of the things we are most certain of in this life. After all, each of us knows that we have a subjective experience of the world.

While many scientists argue that consciousness emerges from the interaction of molecules in our brains (in line with materialism), a minority suggest that consciousness might be a fundamental and ubiquitous property of the universe, where all things are conscious. This is a ‘panpsychic’ (rather than materialist) philosophy. It is a whole different worldview. A completely different way of understanding reality.

As I consider this, I find myself in the haar.

The world shifts.

I know that the landscape has not changed, and yet it has also morphed into something entirely new to me. Something foreign and refreshing and terrifying and intriguing.

But why is it that I find myself stepping into the haar now, after so many years of reticence and hesitance?

Perhaps it is that I have left academia, and from beyond the walls of the ivory tower I have found new freedom. Perhaps it is also the fact that neuroscientists are seriously talking about panpsychism, granting permission to enter the haar (for those of us not brave enough to wade in by ourselves). But, there is something else.

In Fleabag, the priest says, “why believe in something awful when you can believe in something wonderful?” As somebody who has always believed that we end our brief stint on this earth by returning to the soil — body, mind, consciousness, memories and all — I have been thinking about this a lot lately. But also, in tandem, I have been thinking of Douglas Adams’ saying: “isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?”

Exploring different worldviews, I am drawn again and again to these quotes. Am I interested in exploring alternatives to materialism because I want to believe in something beyond what we can measure, or because I genuinely think there could be more to reality than what materialism would have us think? Am I playing in this space because of the joy of it, the curiosity of it, the need to ‘find’ reality, or because of something deeper — a primal urge to believe that death is not a full stop?

I am none the wiser about the answers to these questions. But I am wiser, I think, for stepping beyond what I thought I knew. For wandering into the haar. For letting my landscape shift and slide, and meeting the haar in the magic of metamorphosis.

Opening minds, opening doors, opening perspectives, unfolding ourselves and allowing ourselves to reform, reshape — this is, I am learning, what wisdom may really be about. Not answers, but exploration. Not what you find in the haar, but being willing to walk into it in the first place.

… that, and coming home from the thick body of the fog to a warmly lit kitchen, my partner baking bread, my dog wagging his tail, and knowing that no matter what the world may or may not be, no matter which reality we may or may not exist in, this is what really matters.

This scene is the whistle of the periwinkle, calling me home.

I was thrilled to nominate the incredible poet and artist

for ’s ‘best words best order’. Her reading is delicious. You can listen at the link below.If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

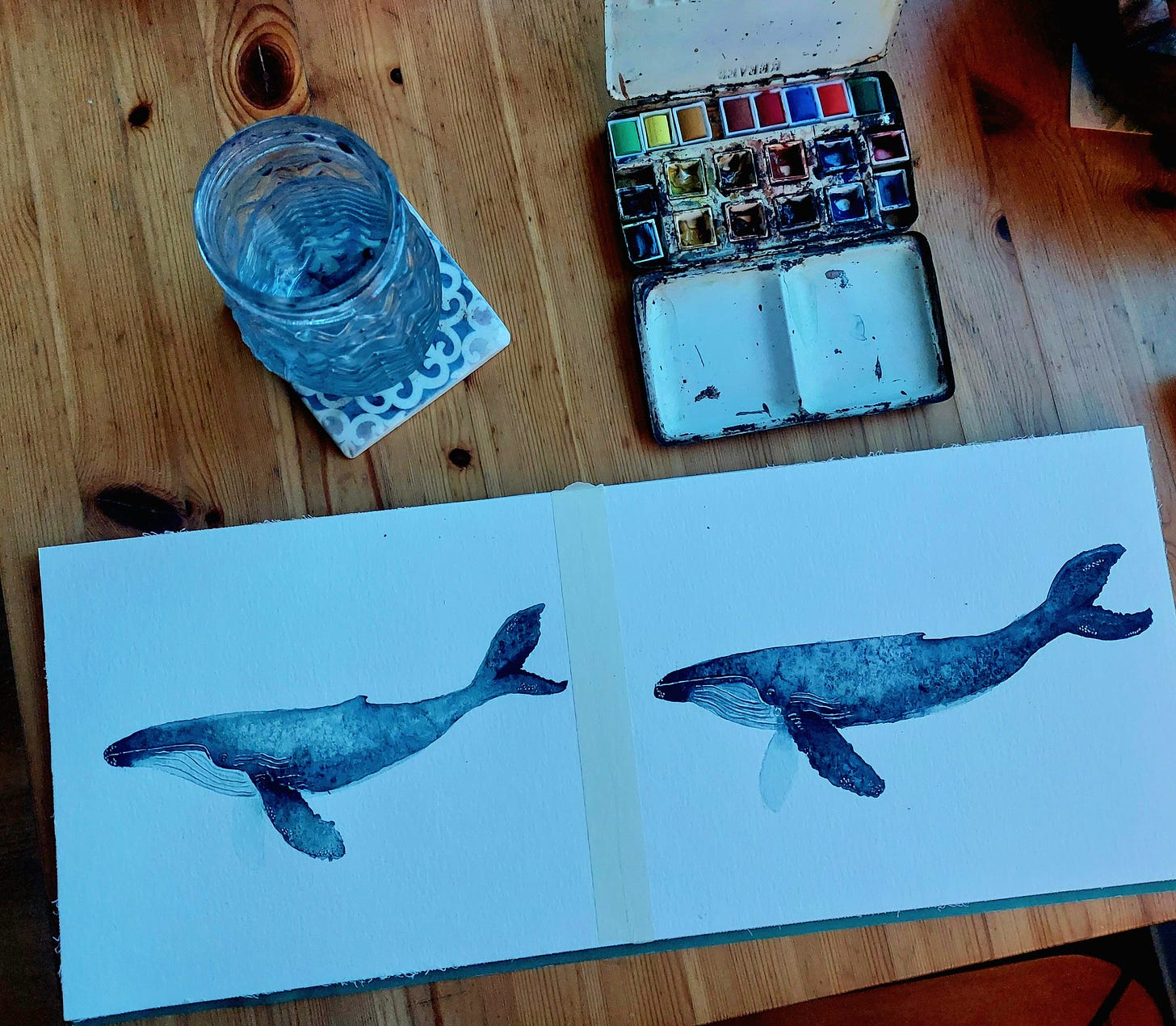

If you’d like to become a founding member of this substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

In my 20s I lived on an island in Maine and studied ecology surrounded by haar. At night the borealis blessed the sky. Being pathologically curious I learned their mechanics but still regret knowing - like a child with no presents left to open. Science is valuable and yet as Oliver said we live with mysteries too marvelous to be understood. To keep our distance from those who think they have the answers. (Mysteries, Yes). I am finishing medical social work training and spent the year in oncology struck by this. A cancer clinic is a temple to science yet again and again I see patients benefit as much from empathy as chemo. Thank you for another Sunday morning treat.

This is entrancing Rebecca. I have not experienced the Haar, but my imagination is dreaming its wonder up in my mind. I think perhaps part 2 of my Earth Day story might include it.. after reading this, I wonder if drawing and writing might feel like being lost within it. I often need to be called back from the disorienting space I have been lost within, by the sound of a metaphorical periwinkle whistle of family and home. I have believed for most of my life in the empirical, but in this latest decade of my life, I have found a different level of understanding, and although I do not believe magic is real, I also know that it is. Thank you for writing so beautifully week after week, and giving me more evidence to know that it is.