home scar

on small and limitless joys

I’ve never really paid attention to limpets. They are the quiet child on the side-lines of a raucous birthday party: tucked away, regrettably easy to ignore. Still, I have been known to pocket the odd washed-up shell and ferry it home to add to my collection of small and beautiful things—recently I even found one at the bottom of my underwear drawer (I don’t know how it got there; our house is full of such mysteries). But the other day, something happened that made me fall head-over-heels in love with limpets—an immediate and permanent sort of love, the sort that means they will now forever occupy a corner of my heart.

What happened is this: my partner, upon seeing my hair tied in a topknot one morning, said, oh, like the fish, and I said, huh? And he told me of a fish called a topknot; he’d seen it in our rock-pooling field guide. I found the book, looked it up (a flatfish, Zeugopterus punctatus), and then, as always happens when I open a field guide, I had a flick-through, stopping to read about whatever caught my attention. And the title THE SECRET LIFE OF THE COMMON LIMPET: HOME SCAR caught my attention.

Home scar.

That phrase alone was enough for me to fall in love; cosy, violent, visceral, it is poetry1. But also, the home scar itself is poetry. Let me explain.

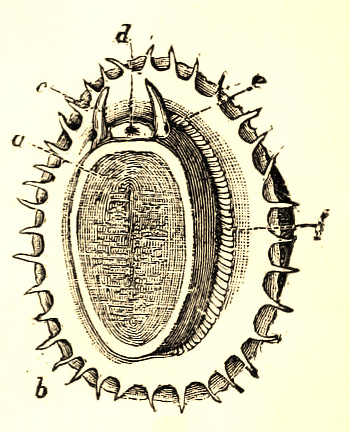

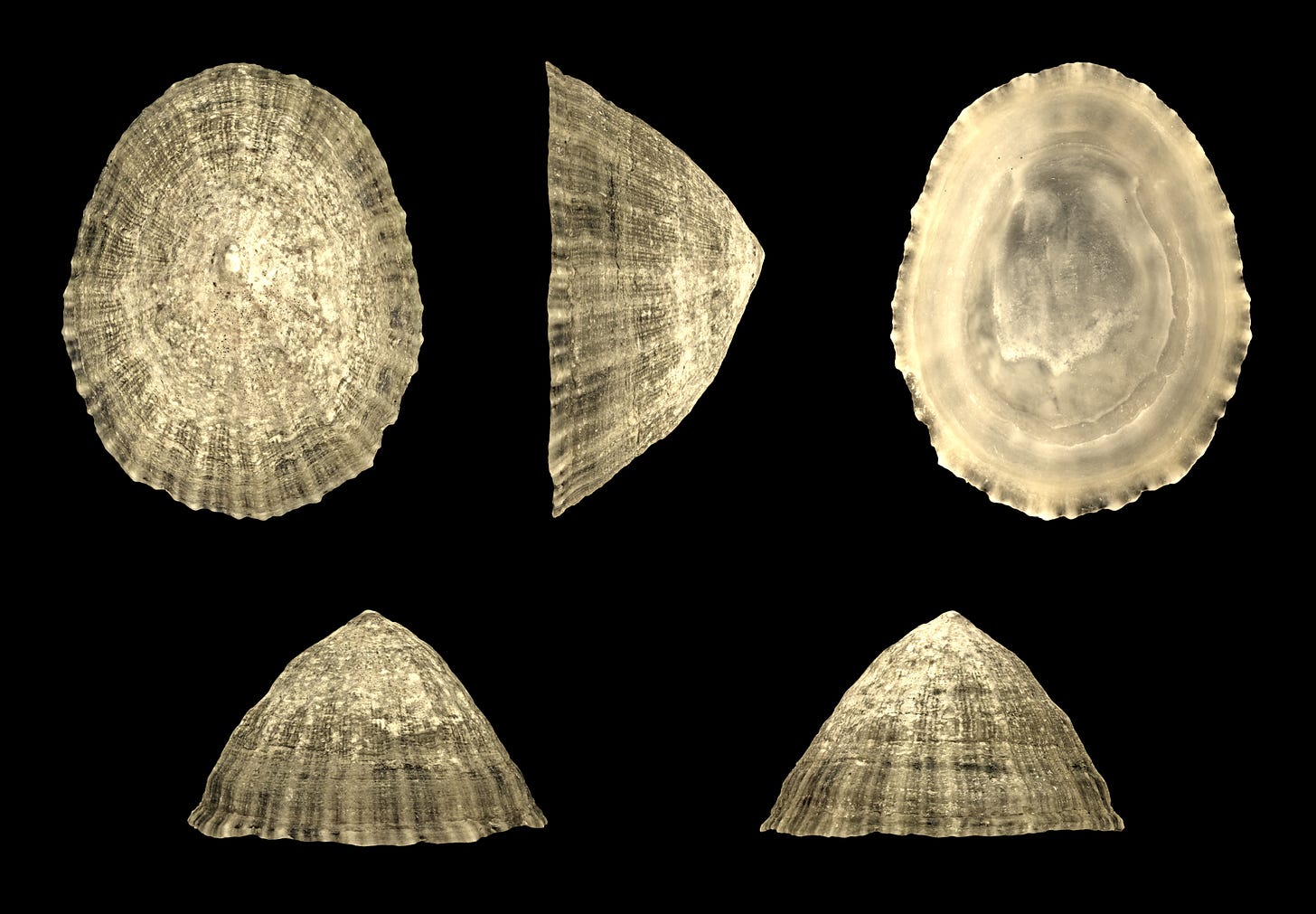

After a few days existing as planktonic larvae, limpets (a type of mollusc, related to snails) choose a rockpool to spend their young lives in. Then, when they are big enough, they venture further up the ‘intertidal zone’ (the part of the beach that is exposed at low tide and underwater at high tide) and choose a spot on a rock that will become their permanent home2. On this spot, they clamp themselves down with their muscular ‘foot’ and the force of their shell against the rock etches a perfect outline of themselves into the stone.

The limpet will move back and forth from this spot in order to forage (they eat algae), but will always return to this exact location, this outline of themselves, and, over time, the outline deepens and deepens such that an obvious scar forms on the rock. A home scar.

It is an adaptation, this home scar, not just a by-product of choosing to go back to the same spot every day. By creating a perfect outline of themselves, the limpets can form a watertight seal between themselves and the rock. This means they can trap water inside their shells, and they therefore avoid desiccation when the tide goes out and they are exposed to the heat of the sun. So this scar in the rock that they create, it protects them. The home scar is safety. It is comfort. It is survival.

Human activity—most notably ocean acidification—does, sadly, pose a threat to limpets. It is weakening their shells, meaning they are less able to form scars in the rock. As a result, they cannot create the environment they need in order to survive—cannot protect themselves from sun, from heat, from environmental variation. Oh, the metaphor runs deep, doesn’t it? Their home scar is an etching in a rock, ours is a little blue dot.

Until November 20th, the UK government is in ‘public consultation’ over a new, massive oil field off the coast of Shetland. This oil field (Rosebank) will release more carbon dioxide than the annual emissions of all twenty-eight low-income countries in the world. It will add 250 million tonnes of carbon dioxide to our atmosphere and blow the UK’s carbon budget out of the water. It will, without doubt, decrease the chance of our little blue dot remaining a place of safety for us (humans and nonhumans alike).

It looks likely that the UK government will approve the oil field, but it is not yet set in stone. Through the Stop Rosebank movement, you can make your voice heard. People of any nationality can send a message to Starmer here. And if you are in the UK, please do consider emailing your MP—you can do so quickly and easily here.

After finding out about home scars, I prepared a poetry workshop for local children. As I was walking the strandline, searching for washed-up limpet shells to give to the kids, the thought struck me that every one of these shells would have the perfect, unique outline of itself etched into a rock somewhere close, somewhere on the shores of this island. A jigsaw: one piece a life, one piece a scar.

As I handed out the shells at the workshop, I said this to the kids. To my delight (because you never quite know what might capture a child’s imagination), there were some awed gasps. And, at the end of the workshop, two of the kids asked if they could take a limpet shell home, each holding a shell in the palm of their hand as if cradling something precious, something made of magic, poetry.

If I’m being honest, those moments felt as important, as meaningful, as sending imploring emails to politicians. Just sharing these small wonders. Just sharing these small and limitless joys.

In other news… those of you who’ve been here for a while will know that last spring I signed with my wonderful literary agent, Laura, and I said I’d keep you updated with novel news. Well! I have some novel news to share—but not quite yet. I’ll be announcing the news in early 2026, and I am so excited to share it with you all! x

If you enjoy ‘between two seas’, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This is a reader-supported publication, and paid subscribers/tips allow me to keep writing.

If you’d like to become a founding member and receive an original whale watercolour, you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above. I have three whales waiting to go to new homes!

There is a surprising amount of poetry in field guides. Or maybe it is not so surprising; the world is, after all, a menagerie of magic.

For up to 17 years! See, magic!

Wow I didn’t know anything about limpets and I too am completely charmed by the idea of a home-scar. I will be thinking about this all day now.

I’ve loved limpet shells since childhood, and I still keep them around the house among other shells. It’s fascinating to learn more about their little lives. I remember seeing time-lapse footage of them moving about to forage, but I had no idea about the home scar. Thank you for sharing.

And thank you for the information about Rosebank. I’ll sign the petition and write to my MP, though I admit I’m losing hope that our leaders truly care about nature. Everything I’ve supported, signed, or written letters about just seems to go ahead regardless of the cost to nature. Still, I won’t give up.