The clouds have been greedy these last few days; they have swallowed all the colour from the land. Even the sea, usually a thousand liquid hues, has been static as a glass eye. Every vista is flint and steel. I am hungering for colour.

The roads are flooded and have been for days. It has rained and rained and rained. I tiptoe my way along muddy banks, trying to avoid getting my feet soggy. As I keep my eyes to the ground, edging my way around the flood, the wet road gifts the sky back to me: layer upon layer of grey; the promise of water from all angles.

A northerly wind gusts, arctic on its breath. By the time I get to the northern shore, my cheeks are so numb they could belong to someone else.

But I am not turning back.

I am going on a treasure hunt.

The northern shore seems a good place to start. In stormy weather, the Atlantic offers up the contents of her stomach and sometimes there is treasure on her tongue. On this beach last winter, beneath a similarly steely sky, I found an oil drum that had rusted to gold, maroon and turquoise. It was a work of art. Somebody else must have thought so too, because when I returned to it (to see how I might get it home), it had been dragged away.

Perhaps we all hunger for colour when the clouds have settled their stubborn bodies in the sky. Perhaps we all become magpies, snaffling whatever bright morsels we can find and ferrying them home.

Give us rusted metal, give us sea glass, give us feathers, shining pebbles, shells. We will adorn our homes and hearts with these talismans; we will stave off the grey until the golden light returns.

But today, the Atlantic has no such gifts for me. All I find is a tangle of kelp and a length of rope. Both are as colourless as the sky.

A magpie is a stubborn creature, though.

I climb onto the shelf of rocks that jut out into the ocean and keep on hunting. It is then – on the grey rocks, beneath the grey sky, next to a grey and violent sea – that I strike gold.

There is a single boulder, tall and square, standing up from a rockpool. It is gold-flecked, gold-cushioned, gold-skinned, gold-scaled. I feel like I have stumbled upon royalty; as if this rock, all dressed up in its crown jewels, might expect me to curtsy.

I go to it, lay my fingers against the gold. It is lichen, and now that I am close I can see that it is not only gold but also a hundred shades of yellow and orange and green. It is a cushion beneath my palm; soft and yielding. In both sight and touch, it is sanctuary.

I learn that the lichen is called maritime sunburst. I cannot think of a name more wonderful. Little pockets of summer. Little bursts of light.

Lichen is a peculiar creature. It is composed of two organisms that exist in symbiosis: a fungus and algae.

To the algae, the fungus offers hydration and protection. In maritime sunburst, the fungus also provides sunscreen. It is this sunscreen that makes the lichen gold.

The algae, sheltered and watered within the scaffolding of the fungus, photosynthesises. The sugars it makes feed the fungus it lives within.

This partnership is ancient. The oldest lichen we have found is about four hundred million years old. And, deliciously, it is a relationship that has evolved over and over again. Fungi and algae have melded into a unique, collaborative lifeform at least three times in the history of life. I love it when such order arises out of the chaos of this world of ours. Amongst all the millions of potential branches evolution could take, these two organisms have come together over and over again. A love affair that transcends unpredictability. I would take lichen over Romeo and Juliet any day.

When it comes to sexually reproducing, this delectable love affair between fungus and algae becomes a little weird (as if it is not peculiar enough already). As they are not a single organism, they do not usually reproduce as one. Instead, the fungus part of the lichen releases spores. These spores only come to life if they land within reach of the species of algae that they can “lichenise” with. And by come to life, I mean that when the spores detect the correct species of algae nearby, they grow arms that reach out towards the algae and scoop it up. A new lichen is born.

Lichens can also get around without sexual reproduction. Creatures that walk over the lichen, like mites or spiders or birds, pick up little parcels of lichen on their toes and spread them around. From those crumbs, new lichens grow.

Imagine it: a spider wandering over this golden rock, picking up a lichen crumb and leaving a trail of sunburst in its wake.

A spider turning a grey world golden.

And in case you have not yet fallen in love with lichens, let me tell you one more thing: lichens are some of the first colonisers of bare earth. This is because the unique partnership of fungi and algae allows them to harvest nutrients from light, air and rock alone.

In the ash after the wildfire, it is the lichens that come back first.

After the retreat of the glacier, it is the lichens that adorn the ground.

When a new island emerges, lichen grows.

And after the lichen comes, nutrients become available for other lifeforms – plants, trees, insects, reptiles, mammals. Entire ecosystems are built on the backs of lichen. This ancient partnership midwifes other life onto the land.

I have long held the view that the workings of the natural world are weirder and far more wonderful than we could ever dream up. Magic and colour and whimsy are around us, always. We just need to look. We just need to go treasure-hunting.

My magpie mind is content, my hunger satiated. This is more treasure than I bargained for1.

If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

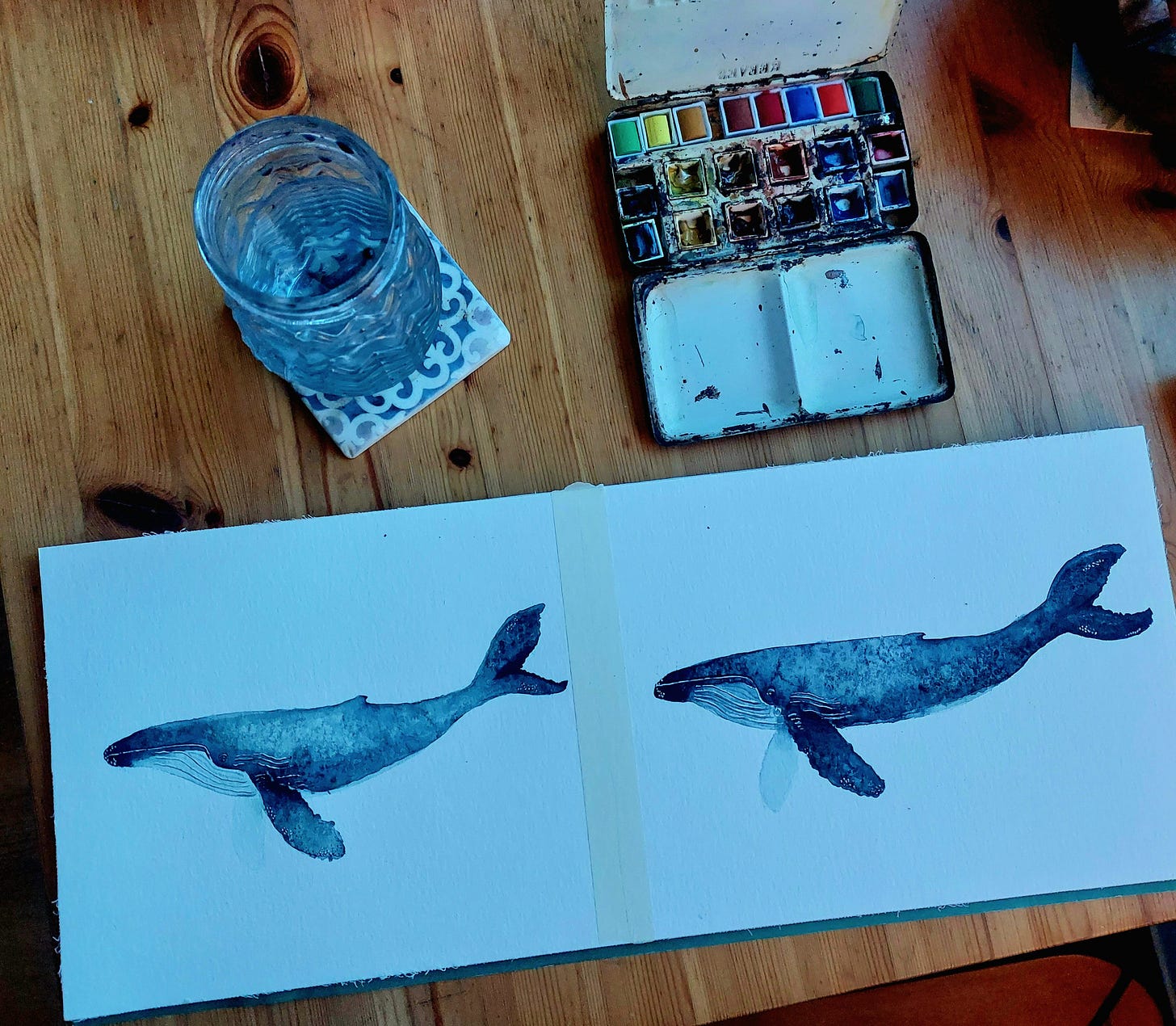

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

since first stumbling upon maritime sunburst, I see it everywhere; it is bursting out from so many corners of this island. It seems there was treasure under my nose along. Sometimes, I suppose, we just have to really look for it.

"Perhaps we all hunger for colour." I've been haunted this week by the story of an American held hostage in Iran starting in 1979. He was kept alone only outside once for 15 minutes in 444 days. He spoke about how he stooped and broke off a blade of grass and hid it in his pocket. That single blade of colour and smell was instrumental to his survival - he could take it out and conjure summer and imagine laying in a field of it. Even the most tenuous connection to the natural world can be a lifeline.

I am enchanted Rebecca, magpies and lichens and treasure hunts... your worlds are like a sweet song in my ears.

I am so lucky to live in a part fo the world where the air is clean (enough) for lichen to grow in abundance. There is a walk I take with my daughter in winter, down a steep path towards a gushing stream where both sides are lined with blackthorn covered entirely in lichen. It is almost luminous at this time of year... the palest of greens imaginable.

Thank you for your beautiful golden and slated variety! 💛