The paths that I walk on this island were once walked by vikings, and long before them, by the people of the neolithic. All these humans have left their traces. On the northern shore are the remains of a viking longhouse, and, just a mile or so west, a neolithic village is buried beneath the dunes.

I think of the echo of these people almost every time I walk the route between the longhouse and the dunes. I wonder what the Orkney islands would have looked like when they wandered its shores, what their everyday life was like, what brought them joy, what made them laugh, what they loved and hated and feared and revered.

In the early neolithic, five to six thousand years ago, this island would have been covered in forest. Where I now walk through livestock and rabbit-grazed fields, dotted with dandelions and buttercups, daisies and clover, the early neolithic people would have known a forested land: woods of hazel, aspen, rowan, willow and birch would have tumbled and tangled over the isle, and within those woods would have been the calls of songbirds—many more than we now have—fuelled by a frenzy of invertebrate life supported by the forest.

But, during the neolithic, those forests were torn down to make way for farmland, and by the time the vikings arrived, there was little forest left.

For millennia, this island has been almost treeless.

It is, in many ways, a biodiversity desert.

But it is hard to hold this thought in my mind for long. Just this morning, as I walked between the viking longhouse and the neolithic village, I saw oystercatchers and herring gulls, ravens and fulmars, seals and hooded crows, butterflies and moths and black-backed gulls. But once, along the very same stretch of land, there would have been too many species to name, and that is what the early neolithic people would have known—a land of tree and wing and fin and flipper, of noise and colour and song. A land hectic with life.

Last night, I spoke with a friend who has just returned from the Amazon. She was telling me of the incredible sounds of the forest. The hoots and the caws and the paws and the howls. I was filled with joy as I imagined it, but there was also a heaviness within me, a sense of unease.

I had, just before speaking with her, read about an entomologist who’s been working in pristine Costa Rican rainforest for decades1. When he first started living in the rainforest, in the 1970s, he had to set up a tent in his living room so that the blue light of his laptop would not attract a tsunami of moths.

Lately, he has not had to do this. Lately, he is lucky if just a few moths fly into his home.

The same is true of the white sheet he puts up in his garden. Once, if he shone a light on this sheet, hundreds of moths would appear from the wilderness surrounding him. Now, just a few arrive.

The bats who live in the roof of his home are dropping dead from the sky, starved of food.

This is pristine rainforest. This is supposed to be untouched land. And this—wilderness becoming a little more silent, a little more of a husk with each passing year—is happening across the globe. The extent of our destruction is no longer confined to the geography of villages, towns, cities, farmland; it is bleeding into places that we thought would be protected, that we thought remained untouched.

I was lucky enough to spend some time working in the Amazon when I was sixteen. Sixteen years later, I find myself thinking of the forest as if it has not changed. I think of the dazzle of moths that buzzed around my cabin in the night, the rustle of insects that erupted with every footstep, the flock of butterflies that licked salt from my skin as I sat by the Madre de Dios river, surrounded by forest that appeared pristine.

But in the sixteen years since I stepped foot in the Amazon—a geological blink, a whisker of time—the rainforest has changed. The biodiversity of the region I visited has dramatically decreased. The forest has been destroyed so that cows can graze and gold can be mined. Wildlife has been hunted. The river, overfished. And even those areas that still look untouched are not—creatures are dying because we are disrupting the climate, because we, on a global scale, are disrupting the delicate balance of life.

Yet there is a part of my mind that refuses to acknowledge this, that imagines only the forest as I knew it, not what I know it must be now. And the same part of my mind also has trouble with this fact: that the rainforest I visited sixteen years ago was already struggling, was already feeling the impact of human activity. I can barely fathom this.

My grandad once told me that when he was a boy in England, he would see thousands of swallowtail butterflies in the summer. Whole fields of them. Beauty everywhere he looked. I can barely fathom this, either. I have never seen such a sight.

Children born today will be unable to imagine the biodiversity we knew in our youth, just as I cannot imagine the swallowtails my grandad knew, just as I cannot imagine what the rainforest was before I first saw it, just as I cannot really grasp the fact that the island I live in is a manmade desert.

There is a name for this: Shifting Baseline Theory2.

What it means is that the world we knew in our youth is our ‘baseline’, our normal. What it means is that we work to conserve what is already depleted, and if we manage to conserve some semblance of these already-depleted lands, we call it success. What it means is that, with every generation, we slip further and further into crisis, and we barely even notice.

Notch by notch, the world becomes a little more silent.

Notch by notch, we become surrounded by desert, and we call it wilderness.

Sometimes, as I walk the coastal path between the viking longhouse and the neolithic village, I like to flip Shifting Baseline Theory on its head. I like to ask: what would the people of the neolithic have thought of the world today, compared to the world they inhabited?

Those people knew a world in which humans could influence their direct environment, but not a world in which humans could influence an entire planet. What would they think of the fact that the sea is warming and the weather is becoming more severe and the entire earth is heating up and even in the most untouched and wild places—places unseen by human eyes—animals are dying, and it is all because of us?

Perhaps they would be proud that their farming practices have nurtured countless generations. Perhaps they would be astonished at our achievements. Perhaps they would be swept away by what we have become. But perhaps they would also grieve for all that has been lost in the course of progress.

And perhaps some of them—the ones who delighted in the tangle of forest, the songs of the birds, the buzz of the insects, the wonder of life beyond human life—perhaps they would not see today’s world, a world that becomes a little more silent with every passing year, as something to celebrate at all.

If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

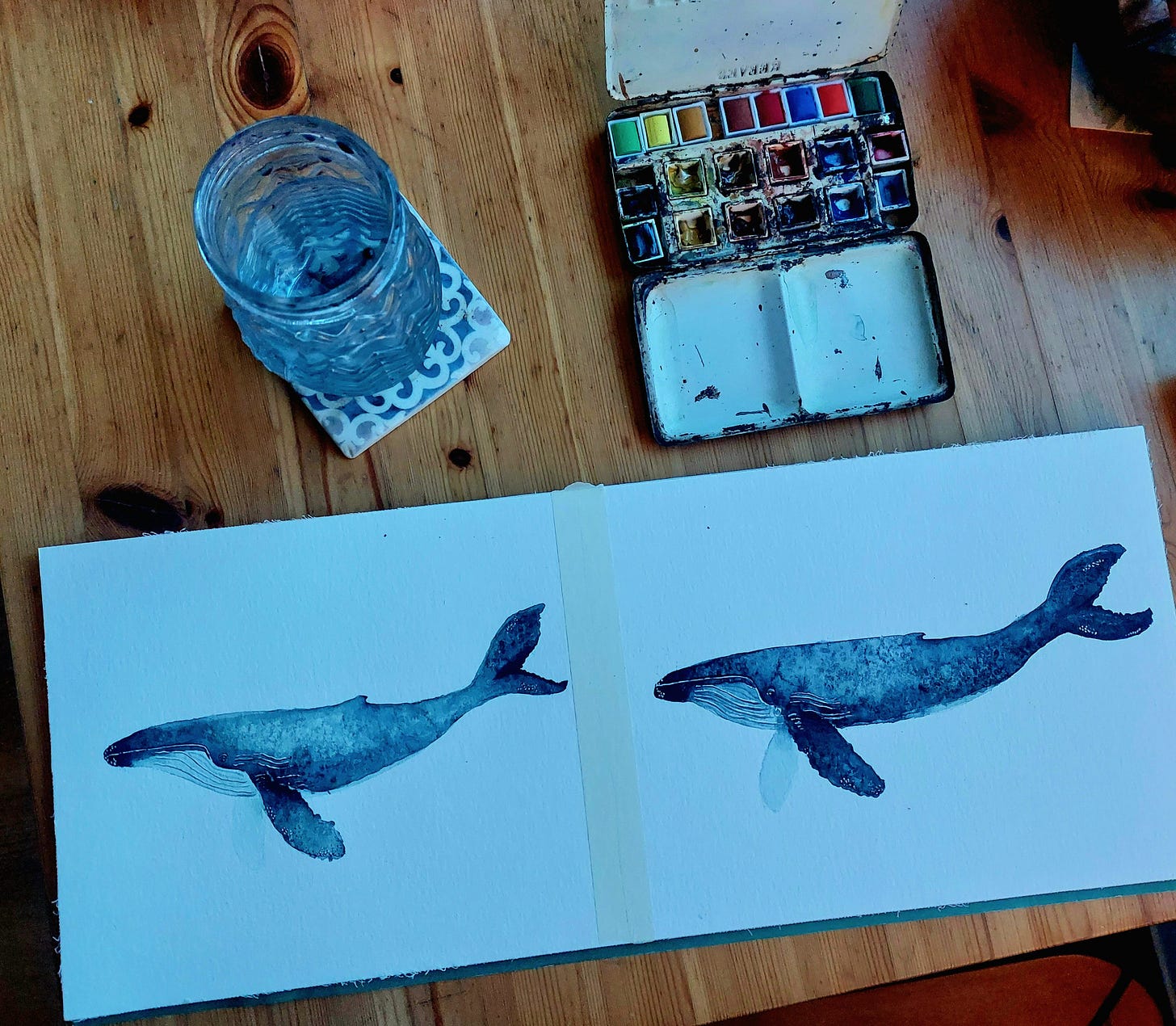

If you’d like to become a founding member of this substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

I am filled with such deep sorrow at all that has already been lost, consumed, destroyed, by humanity. I wonder if.. I hope that we can find a way… that somehow, there could be a way to recover, restore… for us to live in balance and turn back the tide of destruction.

In the 1970s I used to walk home from school (in the Mount Lofty Ranges) along a bush track. In the season there would be so many wanderer butterflies I would have to cover my nose and mouth so as not to breathe them in. They are admittedly an introduced species here, but their present absence (I occasionally see just one making the rounds of the garden) fills me with sadness and concern. The track has been macadamised now, and is encrusted with soulless houses. So it goes.