Silver-strutting babblers, feathered sky-chatterers, church-tower-loiterers, lake-eyed people-watchers. And always, no matter the day, dressed up in their Sunday best.

For those unfamiliar with the jackdaw, they are the smallest UK crow species. Found in Europe, North Africa and Asia, they are as comfortable in our woods, our villages and our farmland as they are in our cities.

They are wary of people but they are also people-watchers. They recognise individual human faces, remember those who are dangerous, and distinguish man from woman.

They have the same number of neurons as primates, but packed into a much smaller brain.

And I love them.

I spent four years and many hundreds of hours watching them in the wild and through little spy cameras in their nests. I extracted and sequenced their DNA, reconstructed their family trees (and with it, their family dramas – and what dramas! One day, I will tell you about The Wasp), and explored their relationships.

But really, it is no surprise that I love these creatures.

We humans have a habit of falling in love with anything we gift our attention to.

Magic is everywhere – and we find it when we dig.

I want to tell you about my life with the jackdaws, but it is difficult to put it all into words.

The long, drizzling (occasionally brilliantly hot) Cornish springs spent climbing up and down precariously-placed ladders to get to their many hundreds of nests.

The joy of watching the wild babies grow from peculiar little beans into beautiful, clumsy chicks – blue eyes wide open, wings stretching in preparation for sky.

The heartbreak of their starvation (and it is natural, that a significant proportion of jackdaw chicks starve).

The heartbreak of their accidental deaths (the two strong, cheeky chicks who fledged out of their nest and right into a bucket of water. We found them drowned there, feathers glinting beneath a wide-eyed sun).

The joy of hearing all the babies of the churchyard and the farmyard and the woodland begging from the treetops.

The eager zigzagging of the parents in and out of nests.

The busyness of it all, the exhaustion of it all, the life of it all, the death of it all.

Those springs taught me more than anything that has come before or after.

For my research, I was asking many questions of jackdaws – but all of them were focussed on the evolution of avian relationships and cognition.

I’ve been fascinated with the experiences of animals – the lived experience, or what we might call the “inner” experience – my whole life. I am pretty sure the root of this lies in my neurodivergence (and also my nosiness). I have long been aware that my brain works a bit differently to many other peoples’, and – from a very early age – I became fascinated with this variation, always asking: but what is life like in somebody else’s mind, in somebody else’s body?

Those early questions led to a lifelong love affair with trying to figure out how we can actually answer those questions (although, as with so many things in life, my main learning from this venture is that it is probably impossible – but ah! The magic of that! Of hunting around for answers and only ever finding little gleaming clues!)

Anyway, I want to tell you about one specific question I was asking of the jackdaws, because my latest research paper (and the last of my PhD) – in collaboration with fellow first author Luca and the rest of the jackdaw team – came out last week1.

One of the questions I was trying to answer in my PhD was exactly what a jackdaw relationship looks like. We knew before I started my work that they form lifelong pairbonds, but we did not have a good idea of what goes on within the pair.

Hence, spy cameras in their nests.

Hence, hundreds of hours spent watching how they interact (which was a bit like watching a soap opera but in a totally unhinged way, with a notebook and a huge list of precisely defined behaviours and a willingness to watch for days, for weeks, for months at a time).

What I found is that every jackdaw relationship is different. While they are mostly faithful birds (as I said, I will write about The Wasp and his adventures another time), some pairs are just not that interested in one another. They do what needs to be done – build their nests, raise their offspring – but that’s pretty much it.

But others (my favourites) are like human couples in the honeymoon phase. For years. For years and years. The honeymoon never ends. They are all over each other. They snuggle, they chit-chat, they preen one another, they spend a lot of time together. And it’s not exactly all or nothing, but the pairs who do a lot of one couple-y behaviour tend to do a lot of all the others. Snugglers, for example, are usually also chit-chatterers.

Earlier in my PhD, before quantifying “pairbond strength”, I tested whether jackdaw partners offer consolation to one another after a stressful event.

I’d been excited about this experiment, although I see now – retrospectively – that the foundations of this question were rooted in quite an anthropocentric worldview. I’m not sure I was really asking this question from the point of view of the jackdaw, but rather from the point of view of a human eager to show our similarities to other species.

Anyway, it turns out that jackdaws do not offer consolation to their stressed partners. They actually do the opposite: they somehow pick up on the emotional state of their partner, and – upon finding out they’re stressed – they scarper (probably to avoid also being exposed to whatever stressful thing happened to their partner).

I started to wonder, after quantifying pairbond strength, if pairs that are more closely bonded are better able to pick up on their partner’s emotional state (even if they do not respond to that emotional state with consolation).

The answer is yes. In brief, what this means is that jackdaws who form strong bonds with their partner are also more attuned to their partner’s subtle shifts in mood.

I think there’s something pretty extraordinary about that. Not that jackdaws have this level of variation and complexity in their relationships, but that this variation and complexity exists all around us, and that we are still just scratching at the surface of it. That the world, despite being mapped and analysed and dissected by humans for millennia, still holds delicious morsels of mystery.

Sometimes, when the world feels too heavy, when the news is drowning all the light, when the brutality of life feels a little too much, I think about this. About all the many delightful mysteries left in this world; all the very many little critters we share our planet with who have their own wonderfully rich and complex lives.

It is a tonic, to feel so small; to feel like a part of something so much bigger than ourselves.

Studies that interrogate how animals live their lives, that circle around what the inner life of a nonhuman might look like (and never getting there), are vital for more than this perspective, though. They are also needed so that – in this extractive, hierarchical society of ours, this society that will ignore the needs and experiences and pain of any creature it is allowed to, human and nonhuman alike – we can protect animals.

By researching the lives of animals – their friendships, their intelligence (which nearly always looks very different to ours but is nevertheless astonishing), the way they perceive the world, their sensory landscapes, their roles within ecosystems, how they might feel – we shine a light (an empirical light) on how animals exist within this world.

We prove things, so that someone can’t say that they don’t believe it to be true, and therefore treat animals as if [they don’t feel pain/they are automatons/they do not need enrichment/they do not need social relationships, etcetera].

One example of where this sort of research has made a big impact is in lobsters and crabs. Studies have shown that lobsters and crabs are highly likely to be sentient, and because of this research, these animals are now formally recognised as conscious in UK law. This means it is illegal for them to be boiled alive (an “undoubtedly excruciating” death, according to experts)2.

I don’t see many jackdaws on this island, but recently one has started visiting a neighbour’s roof. I watch it each day, waiting for another to show up at its side, wondering what sort of partner this little one will be – how affectionate, how attentive, how responsive. And I wonder how it feels, for this jackdaw to be alone, to be out here on this wild and windswept island without another jackdaw in sight. But we will never quite know what it feels like to be inside another mind. We will only ever circle, digging up little morsels of insight here and there, holding our knowledge to the light and wondering at the ocean of magic that lies beyond it.

And, finally, on the topic of the joy of being small, a poem -

If you enjoy between two seas, would you consider a paid subscription, or leaving a tip? This allows me to keep writing and sharing.

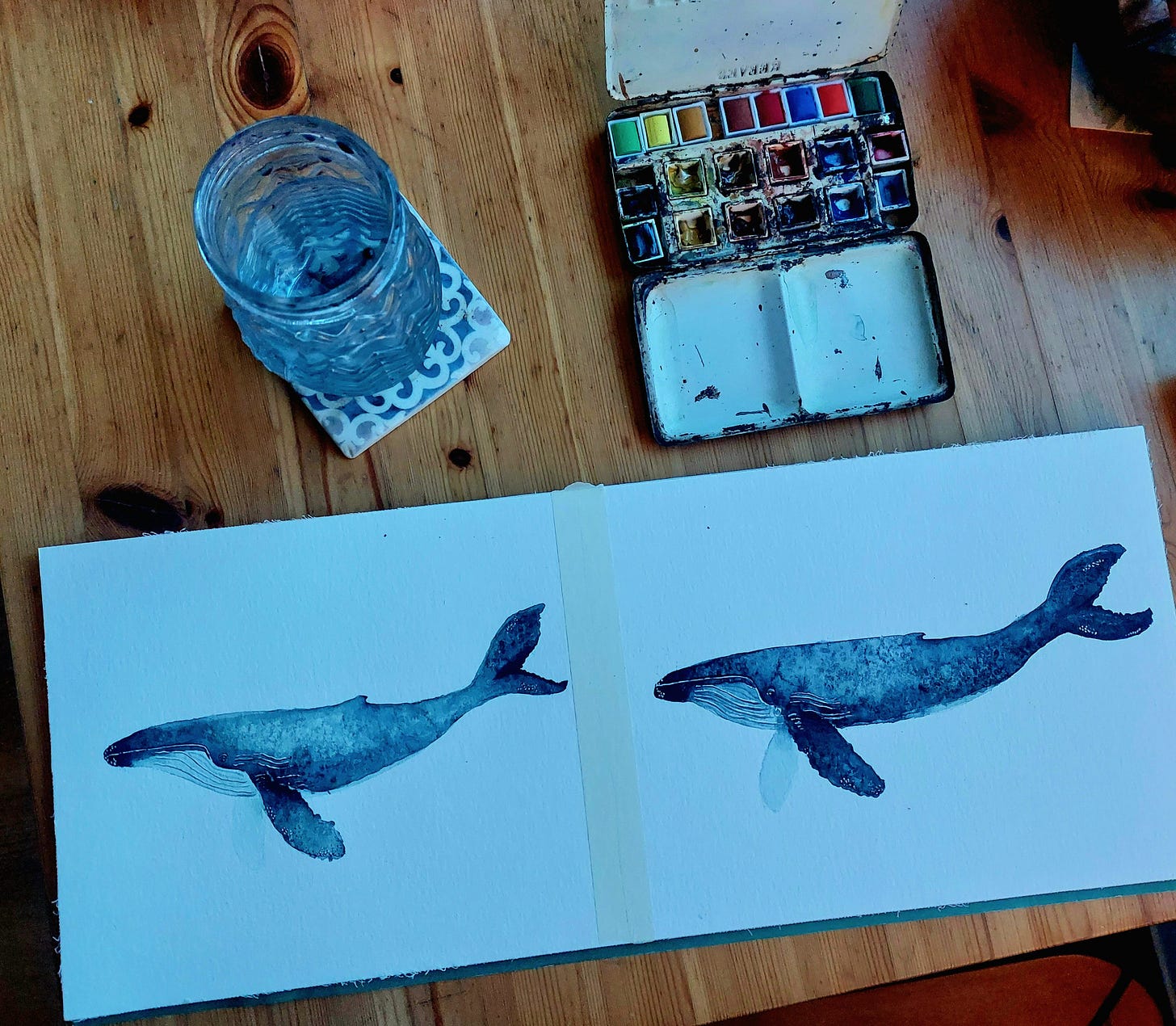

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling substack (and receive an original watercolour), you can find this option by clicking subscribe/upgrade above.

Unfortunately, they are still being boiled alive, but the path is being paved for this practice to stop.

Jackdaw photo by Łukasz Rawa on Unsplash.

Audio backing from Jack Berteau, https://xeno-canto.org/explore?query=western%20jackdaw

i recently moved house and have been gifted with a whole clattering of jackdaws ! They are wonderful characters - thank you for helping me understand them more..

Congratulations on your publication, Rebecca. It really resonated with me, what you said about neurodivergence and curiosity about the inner lives of others. Beautiful essay, once again.