The skies have been heavy this week, the air icy, the snow skittish and flurrying. I am sitting in the living room, trying to find words that will not come, when my phone buzzes.

Killer whales by the pier.

In a blink, the muted weight of the day metamorphoses into something electric. I jump up, shout to my partner that the orcas are here, and we stand at our living room window scanning the harbour, the pier, the strait between this island and the next.

Another message appears on the island chat (the klaxon is sounding).

Pod heading north.

Coats half-on, shoes untied, hats and gloves stuffed into our pockets, we jump in the van. The dog jumps in, too, desperate to join the excitement. We drive north. The roads are a little icy so we go slow, despite the need for speed. The killer whales, if they’re travelling, move fast.

At the top of the hill, we meet a neighbour. She’s pulled into a layby, gazing across the water through binoculars. We stop, roll down the window. She tells us she hasn’t seen them yet, they must be further north. We say we’ll try to find them, and off we go.

We drive to the northeastern tip of the island, and as we are going down the hill, looking out towards the strait, we see it: a dorsal fin slicing through the water. It’s a bull, his fin is huge, somewhere between one and two metres if I had to guess. Just as quickly as the fin came, it silks beneath the water again. We both squeal, hearts swelling, hearts beating to the giddy rhythm of whalesong.

We pull into a layby at the bottom of the hill, right next to the water, put on our coats, hats, gloves. The wind is fierce, the clouds heavy with hail and snow. As I hold the binoculars to my eyes, my fingertips ache with the cold. But then, again, comes the bull. This time, next to him, a female. Then, two more. Then another, small, maybe a juvenile. They are close to the shore, slicing through the shallows.

Despite my numb fingers I get my phone out, take my gloves off, send a message to the group. More messages come. People are wrapping up warm, getting in their cars, rushing out into this brutal weather, all for a glimpse of dorsal fin.

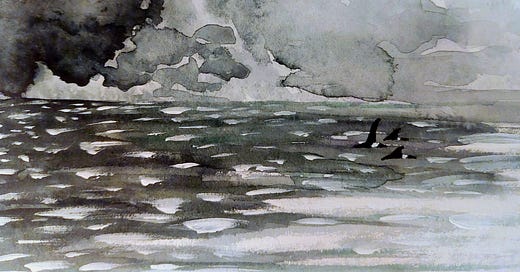

The water is rioting today. There is mist, froth, ink blue, glints of green. But when the whales surface, there is no missing them. They are a shout of black amongst this chaos of colour. They are like a moon, the poem of them, the way they gift the human eye an anchorage.

They come so close to the shore, so shallow, I cannot believe they are still swimming. They are moving back and forth, round and round, and it is clear that they are hunting. These are seal eating killer whales. As we drove past the harbour earlier, I saw more seals than usual gathering behind the pier. I understand now that they are sheltering, weathering the hunt, hoping to live through it.

The whales begin to travel quickly, southwards, back the way we came. We hop back in the van, drive back up the hill. We pass the neighbour who’d been at the top of the hill. She’d seen our message and was on her way to us. We both stop, roll down our windows, decide where best to place ourselves now the whales are heading south. There is something hushed and rushed in our voices.

We see a friend’s car perched on the top of the hill. He is leaning out of his window, binoculars out, scanning the water. We pull up and he comes over, points out where the whales are. We all stand in a row, on this icy hilltop, watching the pod. They are restless. The bull raises his head out of the water. A flock of gulls are circling above him.

Another van pulls up; another neighbour gets out. We point to where the whales are, and the line of humans stood on the hilltop gets a little longer on this bitter cold, electric morning.

And then the coastguard stops as he drives past, asks what we’re looking at, peers out to the whales. After him, a removals van stops and the two guys inside ask what on earth we’re all doing. They’ve never seen killer whales before. Someone lends them binoculars. They whoop and squeal just as we do. And then comes another car, four more people, binoculars passed around, more whooping, more squealing. A line of hearts filled with wonder.

This is the power of the wild. It nourishes the children within us. It reminds us of the ecstasy of being alive.

A raven flies in front of us, inspecting this line of hooting, smiling, freezing apes. I don’t know if bemusement is in a raven’s emotional repertoire. If not, this individual does an excellent imitation.

The orcas are getting more and more excitable. One slaps its tail against the surface of the water. A collective “aahh” comes from all the humans on the hilltop, our hearts beating to the rhythm of the hunt, the hunters. And then a whale’s head emerges, strong and fast, and in its mouth a seal, and then they are both gone again, back underwater. The gulls are circling, descending, coming in to steal what they can. The whale’s mouth comes back up, the seal still in its jaws, and then it is gone again and all we see is splash, fin, tail, blow.

This is the time of year that grey seal pups are left by their mothers; forced to fend for themselves. On the south of the island, a rotund pup has taken up residence on a grassy verge next to the pier. On the north of the island, on my dog-walking route, a seal pup has decided that a sandy dip next to the footpath is a good place to embark on its lonely adolescence.

I think of these blubbery babies, moon-eyed and downy, as I watch the whales with their kill. This hunt is thrilling and wondrous and heartbreaking all at once.

The sky becomes a shade darker. The wind a fraction fiercer. The whales, now the hunt is over, are calm.

Bloody fantastic, someone says as we finally start to disperse. And it is. It is as if we have been handed a perfect little pocket of awe to see us through this bleak winter week.

Later, in the harbour, the seals are still sheltering.

They are on high alert, their gazes wary. I try to imagine it: the moment my moon-eyes see a dorsal fin slicing through water, the moment the head of an orca shoots up from the depths towards my soft selkie skin. My heart feels a quake of their terror, a squeeze of their fear. It beats, for a moment, to the rhythm of the hunted.

Sometimes I think this is the most beautiful and most painful part of being human - the distance our hearts will travel to meet another’s: joy for one, fear for another, wonder and terror all tangled up together.

The wild has no clean lines.

Reader, thank you so much for being here. My newsletter is free, but if you can afford to support my writing financially, I would really appreciate it.

If you don’t want to pay for a subscription but would like to pay a little something for this article, you can tip me instead. Any amount is hugely appreciated.

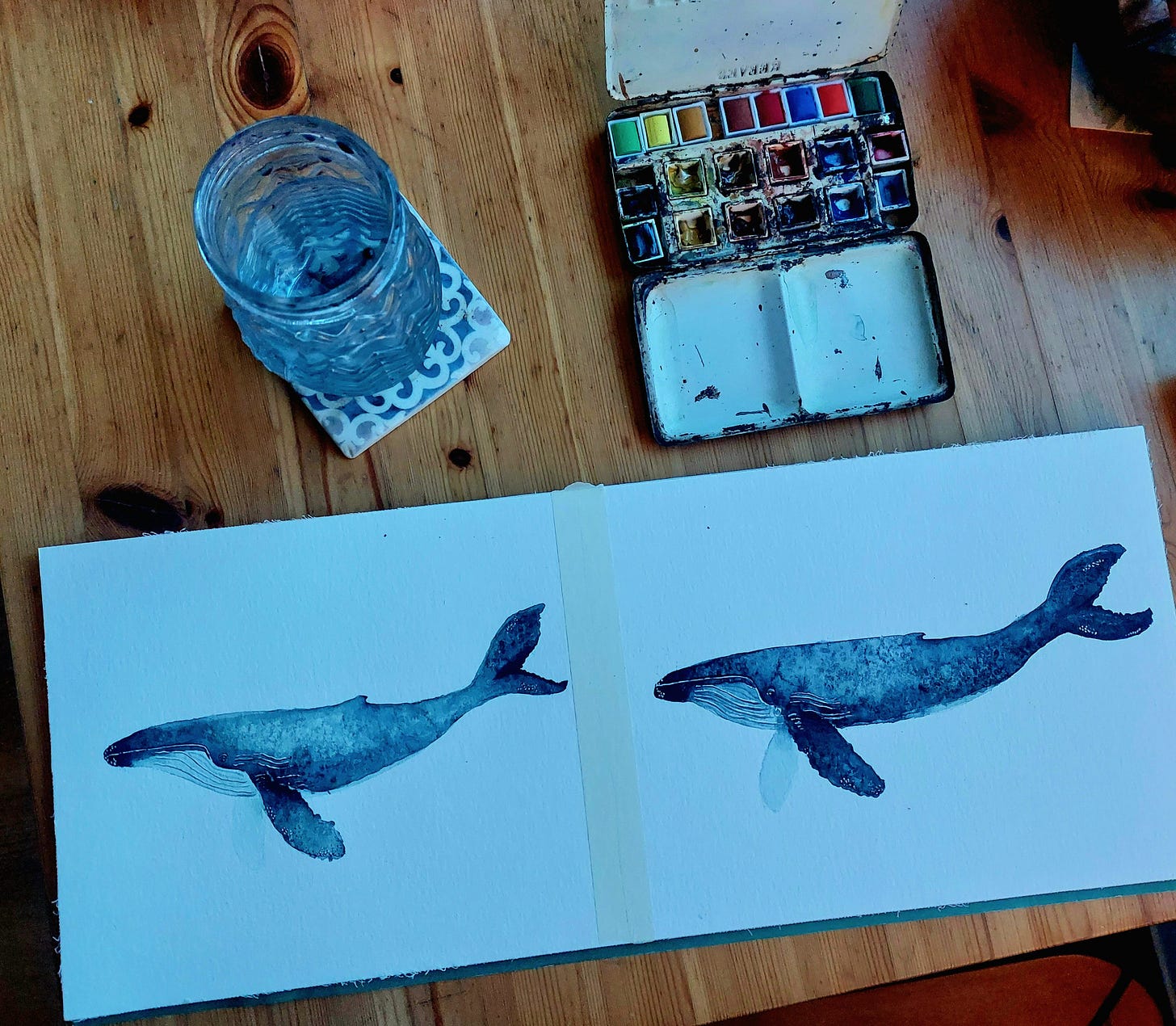

If you’d like to become a founding member of this seedling Substack, you'll receive an original watercolour and some treasures gifted to my island by the North Sea (and my gratitude, of course!). You can see the founding member option by clicking the subscribe/upgrade button above.

'This is the power of the wild. It nourishes the children within us. It reminds us of the ecstasy of being alive' ⚡

One moonless night after driving for hours we tossed our tent on the shore of a pebbly cove in the San Juan Islands, WA. Around 3am we woke startled to loud breathing/scraping/splashing at our door. Fear! Was it a bear? Someone coming ashore? By flashlight we could see the entire bodies of the orcas gleefully rubbing themselves on the pebbles a car length away. Felt like you could touch them. Perfect little pocket of awe.